The last column I wrote for Northwest Book Lovers was a guide to discovering international literature, which is an interest of mine. Carrying that a little further, I recently interviewed German translator Katy Derbyshire, who I first met online when I was tracking down an excerpt of a yet-to-be-published book. I’m friends with her on Facebook and she posts some really funny things, so I thought she would make a good interview.

Derbyshire studied German at Birmingham University and earned a diploma in translation from the University of London. In 1996, she moved to Berlin. She translates contemporary German literature and blogs at lovegermanbooks.

GC: I loved what you did with The Shadow-Boxing Woman. How do you get translation projects?

KD: It’s quite hard to get translation projects actually, because, of course, not many books get translated into English. So either you wait for a publisher to offer you a book or you get pro-active about it. In the past I pitched German novels to publishers, made up a whole dossier with sample translations, reviews, information, photos and so on. That wasn’t very successful, but I suspect because it was like cold calling. If the people didn’t know me, how could they trust my taste? So now, a couple of years on, I read books out of interest but always with an eye toward whether they’d work in English. And the ones I love I suggest to the publishers I have contacts with. Sometimes it even works and they commission a translation. That’s what happened with Simon Urban’s Plan D, the book I’ve just finished translating for Harvill Secker in the UK. It should be out next spring there and I’m keeping my fingers crossed that an American publisher will snap it up, too.

KD: It’s quite hard to get translation projects actually, because, of course, not many books get translated into English. So either you wait for a publisher to offer you a book or you get pro-active about it. In the past I pitched German novels to publishers, made up a whole dossier with sample translations, reviews, information, photos and so on. That wasn’t very successful, but I suspect because it was like cold calling. If the people didn’t know me, how could they trust my taste? So now, a couple of years on, I read books out of interest but always with an eye toward whether they’d work in English. And the ones I love I suggest to the publishers I have contacts with. Sometimes it even works and they commission a translation. That’s what happened with Simon Urban’s Plan D, the book I’ve just finished translating for Harvill Secker in the UK. It should be out next spring there and I’m keeping my fingers crossed that an American publisher will snap it up, too.

Another more classic route is writing reader’s reports for editors. Basically, nobody in English-language publishing can read any foreign languages, so if they get sent a German book by an agent or a scout or a publisher, they need someone to assess it for them. So they pay me a very small fee to read it and report back, and if I like it and they like what I say about it (they often ignore me, though), they tend to ask if I’d translate it for them, too. A bit of a thankless task, except that it feels very good to spend all day reading on the sofa and get paid for it.

The third case is my translations for Seagull Books. They work in a very different way, encouraging  their translators to bring books to them. So if there’s a book I really love and I know it would suit their catalogue, I talk to them about it and they say pretty much, “OK, let’s buy the translation rights.” Which is amazing. It’s like they’re the antithesis of British and American publishers. No “What do Marketing say?” No “But will it make a loss?” Just trust and enthusiasm.

their translators to bring books to them. So if there’s a book I really love and I know it would suit their catalogue, I talk to them about it and they say pretty much, “OK, let’s buy the translation rights.” Which is amazing. It’s like they’re the antithesis of British and American publishers. No “What do Marketing say?” No “But will it make a loss?” Just trust and enthusiasm.

GC: What’s the first thing you do when you get a text to translate?

KD: Celebrate! Boast to all my friends! And then usually I reread the book (because these things take a while so I’ve probably forgotten much of it by the time the contract comes through). I also try to read around the book a little, read writers I know were influential on the text, read similar genre writing in English, that kind of thing.

I like to contact the author and find out how involved he or she would like to be in the translation process. Most of them don’t have much time but sometimes they want to have more say, and usually they’re very pleased to be getting into English, which is a great honor. Only about 40 novels get translated from German to English every year, so if yours is one of them it must feel pretty good.

Once I’ve procrastinated all I can I just sit down and start translating in my office, which I share with two very quiet non-translators, away from my usual clutter with just a long shelf of dictionaries and reference works collected over the past ten years or so, with online dictionaries, too. And a postcard of the women pirates Mary Read and Anne Bonny on a Jamaican postage stamp.

GC: Is there an overriding directive you follow when you translate?

GC: Is there an overriding directive you follow when you translate?

KD: I think the main rule I have is not to follow any rules, to approach each translation with an open mind. My brain works in such a way that I’ll often have a vestigial memory of how I translated a particular word in the past, or dealt with a particular structure, but that’s something I try to override. Because a lot of translation is about imitation, getting as close as you can to a writer’s particular style in your own language. So you don’t want to carry over someone else’s style to the next writer.

What I’ve been thinking about a lot recently is avoiding cliché. Often I think we stick too closely to what sounds “normal” or “right” in English, and that can easily lead us to clichéd phrasing. We have something called a Translation Lab here in Berlin, where anyone interested in or working in literary translation from German to English can come along once a month and workshop short prose extracts or poems. Recently we’ve been joined by a writer, who raised this point after we’d all nodded and cooed over a particular phrase. I think it was “out of my mind with worry” or something like that. And it was a total cliché! I was so shocked by what we’d done. So that process of imitation, where we imitate English writing, can be a slippery slope, too. If a piece of writing isn’t smooth in the original, we shouldn’t smooth it out in English.

GC: What changes have you seen in translation in recent years?

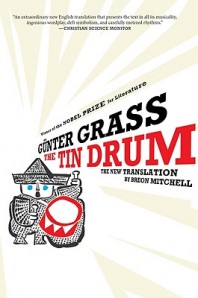

KD: I genuinely believe that translators are getting better, that by working together and communicating in workshops and seminars or  even our lab, we’re improving the overall quality of translations. That’s why we need re-translations or revised translations, like Breon Mitchell’s amazing new version of The Tin Drum, for instance. Because up to about the 70’s or maybe even the 80’s, translators were very isolated and not yet professionalized. And now we have completely different research opportunities with the Internet, obviously, but also a wider network of mutual support. I hope that by getting better and better, we can overcome the prejudice that translations are somehow second-class literature. I get really angry when I read comments like “It sounds like it’s translated from Hungarian.” Wrong! It sounds like it’s badly translated from Hungarian.

even our lab, we’re improving the overall quality of translations. That’s why we need re-translations or revised translations, like Breon Mitchell’s amazing new version of The Tin Drum, for instance. Because up to about the 70’s or maybe even the 80’s, translators were very isolated and not yet professionalized. And now we have completely different research opportunities with the Internet, obviously, but also a wider network of mutual support. I hope that by getting better and better, we can overcome the prejudice that translations are somehow second-class literature. I get really angry when I read comments like “It sounds like it’s translated from Hungarian.” Wrong! It sounds like it’s badly translated from Hungarian.

GC: What’s the hardest part of the process?

KD: Getting the rhythm right, probably. You’re concentrating so hard on the words and making sure you don’t miss anything that sometimes you just lose the rhythm. And then you have to go back and sit there like Stevie Wonder at his keyboard, really using your whole body to beat it out, feel how the sentences resound. Even with prose. Does that sound very pretentious?

I once did a workshop about rhythm in translation, where we tapped out beats on the floor with our feet, real Fred Astaire stuff. I absolutely hate translation metaphors—I am not a ferryman transporting meaning from one bank of a river to another, I’m not a musician interpreting a piece. I’m a translator, dammit. But I do think translators need to go out dancing on a regular basis to train their sense of rhythm. The German translators’ association has a big get-together weekend once a year with a big party on the Saturday night.  A friend and I have been DJing there for about five years now. And you should see those translators go!

A friend and I have been DJing there for about five years now. And you should see those translators go!

GC: At the Edinburgh International Book Festival Etgar Keret said: “Translators are like ninjas. If you notice them, they’re no good.” Sort of like soccer referees. Do you believe that or do you think there should be a hint of foreignness left in the text?

KD: I read that, too, and it got my goat a little bit. Because I think he was in conversation with his American translator, who is the writer Nathan Englander. And, although I don’t see us as being in opposition or in competition, I think writers and translators sometimes look at translation differently. I can imagine if I was a writer I’d be nervous about the translator stamping her own style on my work, so I can understand Keret’s comment from that point of view. It’s still got to be Keret once it’s put into English, not Englander retelling his story.

As I said before, I don’t think there are hard and fast rules—and some writing can really tolerate a little bit of foreignness in translation. Think of W.G. Sebald, for instance. If his translators had made his long, rambling German sentences into standard English we’d have missed out on so much! But there are times when it’s legitimate to give readers an easier ride by smoothing it out a bit.

Also, Englander is already totally famous so he probably doesn’t mind being a stealthy and invisible warrior when he’s wearing his translator’s hat. For me, translation is the only shot at getting noticed I’m going to get. So yes, I do want to get proper credit for my work. And fan mail.

George Carroll is an independent publishers’ representative for university and academic presses, an associate of Seagull Books of Kolkata and an audiobook narrator. He’s also the soccer editor of Shelf Awareness and he blogs at TheCroakingRaven.com.

Thanks for this interview! I found it really, really interesting. I’ve read some of J.R.R. Tolkien’s letters to translators or foreign publishers of his books and I imagine he would’ve been challenging for translators to work with–he had some knowledge of so many languages and so could give them hell if he felt something came across wrong in the translation. I think being a translator must be very interesting work. Neat article.