Teresa H. Janssen {photo: David Conklin Photography)

If you were to have seen my grandmother walking down a sidewalk of Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood during the 1960s or ’70s, you might glance at the slightly overweight, gray-haired, conservatively-dressed woman, and then move on to look at a billboard or shop window. Large black purse in one hand, shopping bag in the other, she would be disregarded, as so many older women are.

If you were to look more closely, you would see the sparkle in her hazel eyes. You might notice the worry lines across her brow, the cross-hatch of wrinkles across her cheeks and mouth, as fine as spider web, and perhaps the thin white scar on the cleft of her chin. Her face bears the marks of a long life, traumatic at times, yet filled with small joys; a life that may not have turned out the way she’d once imagined. But she is a survivor.

One of my favorite deejays, Dalana, at our Port Townsend radio station, ends her Saturday afternoon program each week by reminding her listeners to be kind to everyone they meet. Many carry burdens we cannot see.

I think about that when I hike the woods near home. I admire the incredibly straight trunks of the Doug firs that abound. But what interest me more are the cedar, wild cherry, fir and big-leaf maple whose forms tell stories. Trunks split near the base, deformed by extreme weather (wind, flood, drought) or environmental injury—fire or pollution. Bark scarred by a chainsaw, pocked by bird excavations or insect infestation, mottled by fungi. Branches that crook, like bent elbows. Most fascinating are the burls that bulge from the trunk or roots, like warty lumps. The benign growths form when a tree is stressed. The burl seals off the wound, like a scar, in the tree’s effort to save itself. The bark of a tree communicates its history, it’s struggles and triumphs, just as a weathered face has much to say about a life.

I think about that when I hike the woods near home. I admire the incredibly straight trunks of the Doug firs that abound. But what interest me more are the cedar, wild cherry, fir and big-leaf maple whose forms tell stories. Trunks split near the base, deformed by extreme weather (wind, flood, drought) or environmental injury—fire or pollution. Bark scarred by a chainsaw, pocked by bird excavations or insect infestation, mottled by fungi. Branches that crook, like bent elbows. Most fascinating are the burls that bulge from the trunk or roots, like warty lumps. The benign growths form when a tree is stressed. The burl seals off the wound, like a scar, in the tree’s effort to save itself. The bark of a tree communicates its history, it’s struggles and triumphs, just as a weathered face has much to say about a life.

If you were to have engaged my eighty-year-old grandmother in conversation, you would have realized that she has many stories to tell. Her eyes come alive, but you begin to understand the reasons for her care-worn visage. It was listening to these stories that prompted me to want to write about her itinerant and tumultuous girlhood in the Southwest during one of the most turbulent periods of American history. But all people and natural things undergo stress and pain. It’s part of living.

John O’Donohue, late philosopher and author, writes in his book, Beauty, an entire chapter on the beauty of the flaw. He cites the concepts of wabi in Japanese culture in which the presence of a flaw deepens the character and beauty of an object, and shibui, which refers to the beauty of ageing. O’ Donohue describes how in those we love, the days and years enrich their faces “with ever new textures of presence.” Each human face is a landscape that is “quietly vibrant with the invisible textures of memory, story, dream, need, want, and gift.” Beyond personality and fashion, it’s the soul that makes the face beautiful.

Trees with burls are highly valued. It can take as long as thirty or forty years for a burl to grow to its full size. The pattern and grain of burled wood is irregular and more intricate than ordinary wood and is more expensive because of its beauty and scarcity. Unfortunately, burl poachers will sometimes use chainsaws to cut a burl off of a tree. This can wound the tree and sometimes kill it.

I waited until after my grandmother’s death to begin writing about her life, based on the notes I’d taken and photographs saved. I realized in the process that there were details missing, gaps and inconsistencies in her accounts, and that I’d neglected to ask her many important questions. But I inherently knew that I should not probe too deeply or harm the scars that had formed to protect her and help her survive. O’Donohue reminds me that “no life is without its broken, empty places,” but “where woundedness can be transformed into beauty, a wonderful transfiguration takes place.”

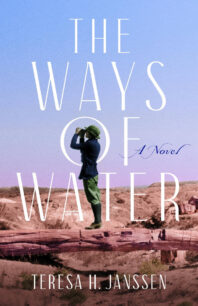

The Ways of Water: A Novel was inspired by my grandmother’s early life in the Southwest.

Teresa H. Janssen with Village Books booksellers Hanna Buehrer and Sophie Richmond

Meet the author at Third Place Books Lake Forest Park (Seattle, WA) on November 15 1t 7:00 and at Liberty Bay Books (Poulsbo, WA) on November 17 at 6:30.

Teresa H. Janssen studied history and French at Gonzaga University and has an M.A. in Linguistics from the University of Washington. She taught history and language for over twenty years in refugee programs, higher ed, and public high school. Her fiction and essays have appeared in a variety of literary journals, including Zyzzyva, Chautauqua, Calyx, Catamaran, Cathexis Northwest Press, and in the anthologies, Art in the Time of Unbearable Crisis and Offerings: A Spiritual Poetry Anthology. Her writing has twice been designated Notable in Best American Essays. Her debut novel, The Ways of Water, is forthcoming November 2023 from She Writes Press. She lives with her husband in Port Townsend, WA, where she writes, hikes, and tends a small orchard.

Teresa during her Authors on the Floor signing at the show with Village Books booksellers Hanna Buehrer and Sophie Richmond