Flannery O’Connor once gave her short stories to a neighbor who read them and said, “Them stories just gone and shown you how some folks would do.” Ten years ago, after hearing a snippet of a story from my grandmother about her step-mother, Hattie, who homesteaded by herself as a young woman in eastern Montana, I was driven to find out how folks like Hattie – shy, frail and unassuming – “would do.”

Flannery O’Connor once gave her short stories to a neighbor who read them and said, “Them stories just gone and shown you how some folks would do.” Ten years ago, after hearing a snippet of a story from my grandmother about her step-mother, Hattie, who homesteaded by herself as a young woman in eastern Montana, I was driven to find out how folks like Hattie – shy, frail and unassuming – “would do.”

That finding-out process took four years, leading to my first novel, Hattie Big Sky, and a burning passion for historical fiction. I became consumed with understanding why ordinary people in the past would go and do the things they did.

I kept coming back to one particular something that someone had gone and done.

Though I’d grown up in Seattle, I was in college before I learned about the incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent during WWII. I was shocked: why hadn’t I been taught about this? It was stunning to learn how quickly pieces of the “relocation” plan fell into place after December 7, 1941:

Though I’d grown up in Seattle, I was in college before I learned about the incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent during WWII. I was shocked: why hadn’t I been taught about this? It was stunning to learn how quickly pieces of the “relocation” plan fell into place after December 7, 1941:February 19, 1942: President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, creating exclusionary zones, paving the way for relocation camps.

March 30, 1942: Two hundred farmers and fishermen were removed from Bainbridge Island.

April 21, 1942: Posters appeared announcing Seattle evacuations within the week.

Can you imagine being given seven days to close up a business, empty your house, find a home for a beloved dog? (Evacuation rule number three: “No pets allowed”)

As a chronic over-packer, there’s no way I could’ve condensed my belongings into the one suitcase allowed. Evacuees had no idea where they’d end up or how long they’d be gone. Would they have thought to pack rubber boots for the spring muck of Minidoka or woolens for the bitter Tule Lake winters?

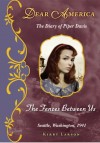

All of this bounced around in my head for many years. Then Scholastic approached me about writing for the re-launch of the Dear America series. They were looking for a World War II story. I had long been thinking about the characters—like 13-year-old Piper Davis— that might walk around in a post-Pearl Harbor world. I quickly said yes.

Aside from a character or two, however, I had no hook on which to hang a story. Despite fast-approaching deadlines, I kept digging, confident that a hook was out there. Somewhere! Then, during one long afternoon at Suzzallo Library, I “met” Reverend Emery Andrews. A minister of the Seattle Japanese Baptist Church, he worked tirelessly on behalf of his incarcerated congregants, eventually moving to Idaho to be closer to them.

It wasn’t until I met Rev. Andrews’ son, Brooks, that I understood the price his family paid for his actions. And I remembered my 13-year-old self who would’ve resented my father’s taking me away from Seattle friends to Podunk, Idaho. Finally, Piper’s story clicked into place.

Brooks graciously made family papers and letters available and introduced me to many people, without whom this story couldn’t have been written.

He wasn’t the only person who helped me nail essential details. Piper’s taste for SkyBars came from my mom’s wartime memories. Men who had been sailors aboard the USS Enterprise cleared up the mystery of how mail was sent and received in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, in the middle of a war.

People I’ll never meet also shaped this book, like those whose stories have been recorded by the Densho Project and the Nisei who volunteered for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, fighting for the country that imprisoned their families.

In my early writing career, my books would never have found readers without “big mouths” like Karen Maeda Allman, Chauni Haslett, René Kirkpatrick, or Cheryl McKeon (hooray for Elliott Bay, Mockingbird, Parkplace, Secret Garden, and Third Place bookstores!). There’s not space here to mention all of the amazing booksellers who have recommended my books. I have to give a shout-out to writer Jamie Ford who deserves a commission for promoting my work. A special woo-hoo to Suzanne Perry at Secret Garden for helping the kids at Laurelhurst Elementary find Fences, leading to the most awesome school visit ever.

In my early writing career, my books would never have found readers without “big mouths” like Karen Maeda Allman, Chauni Haslett, René Kirkpatrick, or Cheryl McKeon (hooray for Elliott Bay, Mockingbird, Parkplace, Secret Garden, and Third Place bookstores!). There’s not space here to mention all of the amazing booksellers who have recommended my books. I have to give a shout-out to writer Jamie Ford who deserves a commission for promoting my work. A special woo-hoo to Suzanne Perry at Secret Garden for helping the kids at Laurelhurst Elementary find Fences, leading to the most awesome school visit ever.

The Fences Between Us won’t inspire Team Piper t-shirts, but it will find an audience thanks to the independent booksellers of the Northwest. I’m grateful to you all.

Kirby Larson was born at Fort Lawton Army Hospital, and except for a short stint in Alaska as a one-year-old, has lived in Washington her entire life. A Kenmore resident, she shares an empty nest with her patient husband Neil and Winston the Wonder Dog.