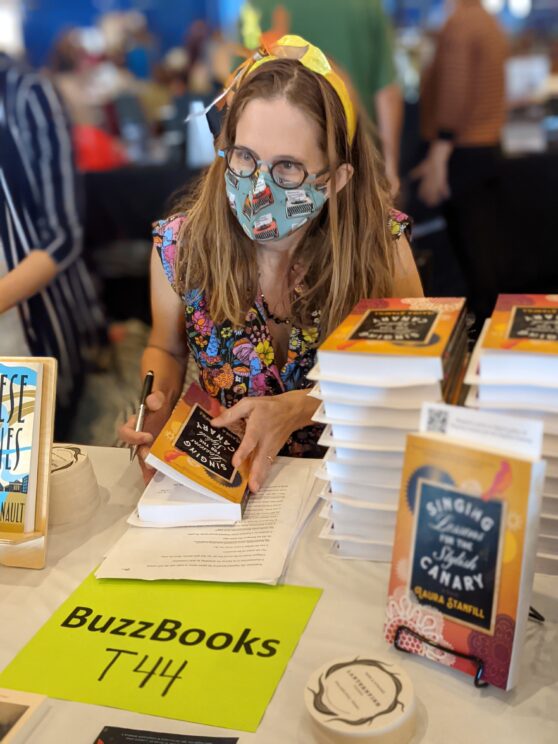

Laura Stanfill signing at Powell’s Books April 2022. Photo by Tracy Stepp

Grace Campbell of Olympia and Laura Stanfill of Portland met at Mineral School in Mineral, Washington, during a 2018 parent residency week.

Grace Campbell is the Fiction Editor at 5×5 Literary Magazine. Her roots are in flash/microfiction, where she has been published in journals like Brevity, Hobart, Joyland, and Midway. Her work has been featured in Best Small Fictions. She is the recipient of literary fellowships, is a Best of The Net nominee, has placed in competitions at Split Lip and Atticus Review, and has been awarded a Pushcart Prize nomination. She is currently completing two full-length works in between snuggling her glorious cats and watching TikToks with her three amazing kids.

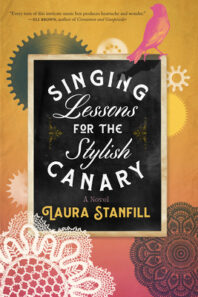

Laura Stanfill is the publisher of Forest Avenue Press. To celebrate the publication of Laura’s debut novel, Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary (Lanternfish Press), Grace interviewed Laura for NW Book Lovers.

The two writers are also appearing in conversation via Zoom at Browsers Books at 6 p.m. on Thursday, April 28. Register here.

I want to start out by talking about how novels become themselves. We tend to place a premium on (not only) ‘firsts’ but on the narratives that contribute to their perceived importance. So this question is about how Singing Lessons began to come into being. Did it start to collect around you in the form of music, lace-making, fairy tales? Did these alternate texts serve as firsts for what became the story?

I want to start out by talking about how novels become themselves. We tend to place a premium on (not only) ‘firsts’ but on the narratives that contribute to their perceived importance. So this question is about how Singing Lessons began to come into being. Did it start to collect around you in the form of music, lace-making, fairy tales? Did these alternate texts serve as firsts for what became the story?

Firsts are so fraught, aren’t they? A literary friend reminded me that although this is my debut novel, it stands in the world on its own as a complete work, and I don’t necessarily need to advertise the newness as a selling point. While I think there’s a special magic about being a debut author, especially when a community is excited about your work, I’ve been writing seriously for decades. Calling this the first kind of cancels the other books I’ve written—two novels, one partial novel, a first draft of a memoir, and a biography-for-hire about a jazz band.

Or maybe cancels is too strong. But for sure this idea of first lessens those other manuscripts’ importance, as each one, too, in its own way was a first. The first novel I never finished. The first one that earned me an agent. The second, which lost me my agent—another first! And so on.

As you know, writing builds on itself. I couldn’t have written Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary when I was new to the craft. Thanks to all the hours I put in, and the amazing teachers and writing group friends who helped shape me, I approached this book with playfulness. Maybe that’s why your question about collecting disparate elements feels so perfect. I had all these pieces, all these ideas, and some attached to each other. Almost like they responded to a particular gravitational force. A pull of my heart, maybe. It’s all a kind of music—the language, the town’s magic, the lacemaking, and definitely the serinette, which was used to train canaries to sing popular songs. The whole novel came together around that historical object.

This project took you fifteen years to write. Does that measure of time feel right-sized to you, in retrospect? Were there factors that prolonged or accelerated its completion?

I had the idea of a book about music-box collectors while pregnant with my now-teenager. Becoming a parent changed me, made me dig deep into my reserves, and ultimately helped me get clearer on who I am and how my brain works. As I grew and changed over those years, the manuscript changed too. Sometimes I went in the wrong direction and followed characters I later threw out. But I think the texture of the novel exists because of the life-work I did over those years, not just the discipline of writing and revising.

Laura Stanfill demonstrates a serinette at PNBA’s Spring Pop-up in Bellingham April 2022. Photo by Brian Juenemann

I was still working on this novel when my second child was born and I founded Forest Avenue Press. She had colic; I needed to do something to keep my brain engaged. Learning to trust myself as an editor of others’ work, and learning publishing from the inside, definitely impacted this novel. Of course, once I started the press, I went through fallow phases with my own writing, thinking that maybe I had studied the craft to help others. Not to be a writer myself. Rejections on my work and accolades for the novels I was publishing made it easy to slip into that sinkhole. Thankfully, I have many friends who urged me to follow my dream, especially Nikole Potulsky, my business strategist during that time. She insisted I put myself into the equation—and only then did I realize I had bent over backwards to be everything to everyone, shelving my goals to make space for everyone else’s.

In the past, I’ve asked authors some form of the question: When did you realize this was the book you had to write? It has since occurred to me that not all literary pursuits are bound up in needing to deliver a particular message or tell a particular story, or even to play with different aesthetic devices through text. Some of what anchors our devotion to a project might, instead, be more about the need to work through a story attendant to, but not specifically the one that plays out in the text. That we might endeavor to feel our way through a story we are needing to tell ourselves. One that can only occur through the telling of another story. Does this resonate for you?

Oh Grace, this is a brilliant question. I came to this project after writing two literary novels that were full of personality and language but they were missing… something. Now I realize I didn’t have a firm grasp of what I wanted to say—the why of my fixation on writing, or on an even more intensely personal level, the why of me. I just knew I had to write. The act of committing to the page, of imagining places and people, felt as essential to my everyday life as feeding myself.

So I think you’re absolutely right; I felt my way through motherhood and launching a business and coming to terms with my fragile health by writing those themes into Singing Lessons for the Stylish Canary. Over the course of the writing, the story I used to tell about myself dissolved in favor of stronger, truer language. My compassion for my characters—their wrong turns, their well-meaning efforts falling short—transformed into compassion for myself. Like Henri, my protagonist, I’ve always wanted to make my parents proud, and I’ve always expected more of myself than what I can actually do physically. In letting Henri struggle and fail on the page, I’ve tended to the vulnerable, sweet child-me in a way that I couldn’t imagine before writing this book. I love him for all his faults, not in spite of them.

Did you have pieces of literary aphorism that you had to eventually put aside? Or ones that became more relevant and true for you?

Did you have pieces of literary aphorism that you had to eventually put aside? Or ones that became more relevant and true for you?

I’ve always wanted to write books that don’t sound like anyone else’s. That drive has pushed me to ignore all kinds of advice and common knowledge about how stories are supposed to go. Many of my explorations didn’t work—like the draft of Singing Lessons where Henri stayed in bed for a hundred pages, being so passive that nobody wanted to read about him—but some of the rule-breaking did stick, like setting up the story with Henri’s father’s birth. I worked and reworked the beginning, hoping to earn that device and inspired by the opening to Elizabeth Gilbert’s The Signature of All Things, which lavishes pages on the protagonist’s father. Henri is who he is because of his family, and I really wanted that context on the page. To earn taking up narrative space like that.

In writing Singing Lessons, you’ve said that you arrived at the liberating notion that you did not have to set upon crafting The Big Serious Novel. Singing Lessons carries what has been described as a whimsical timbre. I’m wondering what tools you employed to maintaining this fairy-tale sensibility.

I’ve always thought of fairy tales as my friends’ domains—Kathlene Postma, who writes feminist ones that are incredibly smart and powerful; Michelle Ruiz Keil, whose YA novels are infused with fairy-tale sensibilities; and Kate Ristau, who is a folklorist, just to name a few women friends who explore this form in unforgettable, imaginative ways.

So I didn’t start out thinking I’d build fairy tales into this book as much as wanting to create a world that honored the object-ness of the serinette. These barrel organs are high pitched like piccolos, and they were used for a social purpose—training canaries away from their natural songs so they might win contests. This inessential, odd, artistic pursuit coupled with the fact that people actually made their livings building these instruments felt like a juxtaposition I wanted to unpack. I found the sound of the book, its whimsy and language, after quite a bit of experimentation. There are definite resonances with the kind of storytelling one finds in fairy tales, especially in how I put the village on the page. But the longer slog was figuring out how to maintain that storytelling style over hundreds of pages and tie it to a plot that builds on itself and eventually resolves into an ending.

So I didn’t start out thinking I’d build fairy tales into this book as much as wanting to create a world that honored the object-ness of the serinette. These barrel organs are high pitched like piccolos, and they were used for a social purpose—training canaries away from their natural songs so they might win contests. This inessential, odd, artistic pursuit coupled with the fact that people actually made their livings building these instruments felt like a juxtaposition I wanted to unpack. I found the sound of the book, its whimsy and language, after quite a bit of experimentation. There are definite resonances with the kind of storytelling one finds in fairy tales, especially in how I put the village on the page. But the longer slog was figuring out how to maintain that storytelling style over hundreds of pages and tie it to a plot that builds on itself and eventually resolves into an ending.

If I had framed the novel as fairy tale adjacent from the beginning, I might have found the form faster, through a more streamlined and efficient creative process. As it was, I experimented, played, reversed course, and tried again. There was a lot of mud-wrestling—whole characters and plot arcs discarded and replaced with new ideas. Months of research for naught. A novella-sized ending consigned to the scrap bin. I miss those characters, but I don’t regret writing them or letting them go. The resulting space let my protagonist grow into himself in ways I didn’t expect, and allowed me to tug the existing threads of the story into tighter, more intricate designs. My awesome editor, Christine Neulieb at Lanternfish, helped me adjust and polish from there.

Stanfill signing advance copies for booksellers at PNBA October 2021

This is a novel about dreaming and being bold, with a decent amount of magic thrown in, but also, it’s a novel about music and the instruments that commodify niche industries like canary training. Talk about the role of music and how you came to source the story through this particular kind of music.

I grew up with mechanical music in the house, because my parents are collectors. Their passions, and how they shaped their lives around attending music box conventions and spending time with friends who shared this special interest, inspired me to dig into that landscape as a writer. What would it have been like to live in a world where you couldn’t just flip on a radio to hear popular songs? Where you had to learn an instrument or have enough social capital and cash to buy a music box, which would earn you a limited handful of songs? The idea of music sounding the same each time through captivated me too, as a former flute player; I used to strive for accuracy and perfection in my playing, but music boxes make songs concrete, fixed on the cylinder.

My previous unpublished novel was set in a newsroom—a world I knew well as a former reporter and editor. With mechanical music, I had only been a tagalong participant, not as an eager member of that community as much as a visitor. My father is also a phenomenal pianist and savorer of classical music. Every room in my childhood home had the tools of music in it—radios, music boxes on display, my father’s piano scales wafting through the rooms, my flute and music stand. When I discovered the serinette, it seemed like a way I could explore my parents’ hobby through themes that matter to me—gender and power, expected family roles, and my lifelong admiration of my dad.

I’m endlessly fascinated by the idea of text as it pertains to non-literary devices and how alternate texts inform not only how we represent them, but also how they come to represent us. Because so much of the story has to do with music boxes, canaries and lace-making, I’m wondering if you utilized these resources beyond enriching the details of the telling, and further, invested yourself in their respective traditions as a way to center yourself more fully in your world-building, and if this journey produced any tributaries of interest that are extra-literary for you.

Writing this book opened me back up to my lifelong love of crafts and handmaking gifts. Music boxes and barrel organs replicate art—turning creatively written compositions into mechanics so they can be played over and over again, exactly the same each time. Over the years of writing this book, organizing craft days for my children and their friends, and especially during the pandemic, I’ve turned to art for pleasure. Not for commodification, as Henri’s family does with their serinettes, but as a way to play with my hands.

I haven’t—yet!—learned the art of bobbin lace, but I’ve dabbled in embroidery and crochet and I’m a longtime knitter. I’ve also found myself making collages, drawing small cartoons, and painting, not with any expectations about their value or quality. Before completing this novel, I focused my time on achievable results—making a scarf, say, for a friend’s birthday instead of knitting for pleasure, the rumination of it. Now I have a lot of unfinished projects around—more than ever. But that’s because I’ve learned to separate the making from the having. The making’s what matters to me right now. Not the finishing. Not the final object. My art practices are all much freer as a result of not insisting on an end product or a reason for the making.

In Singing Lessons, each chapter is headed with an inter-title. Derivative of early film, these features are also a nod to Victorian-era blurbs that grant an almost ironic air of formality and work; a pleasingly vintage feel. Talk about your decision to include these, and how details in structure can work to center the reader in a stylistic motif that strengthens your world-building.

At first I just used numbers as chapter titles. Then I tried all kinds of techniques and gimmicks, including pushing the story to fit the framework of a concerto, with Henri as the soloist. But that felt too artificial, too forced.

After some more exploration, this is the idea that stuck—these summary sentences as titles. I’ve always loved unexpected chapter titles, ones that give a sense of direction without telling the whole story. Vanity Fair comes to mind as one of the nineteenth-century texts that applies this technique as a way to draw readers in. For a more recent example, The Gentleman by Forrest Leo plays wonderfully with the nineteenth-century novel, and it was reading that book—a meticulous homage to an outdated style of storytelling that’s infused with modern humor—that made me realize I could use the chapter titles to convey the personality of the novel, not just as organizational tools. And I wanted to give a sense of where the story was going, like an arrow, story this way, without offering spoilers.

After some more exploration, this is the idea that stuck—these summary sentences as titles. I’ve always loved unexpected chapter titles, ones that give a sense of direction without telling the whole story. Vanity Fair comes to mind as one of the nineteenth-century texts that applies this technique as a way to draw readers in. For a more recent example, The Gentleman by Forrest Leo plays wonderfully with the nineteenth-century novel, and it was reading that book—a meticulous homage to an outdated style of storytelling that’s infused with modern humor—that made me realize I could use the chapter titles to convey the personality of the novel, not just as organizational tools. And I wanted to give a sense of where the story was going, like an arrow, story this way, without offering spoilers.

Has Singing Lessons changed what you read and how you read it? Who are you reading now?

I read a lot of nonfiction titles while researching music boxes and the nineteenth century, but as for a longer-reaching change, I have definitely been drawn to more fantasy and genre-blending books since adding magic to this novel. Not just as a reader but as an acquisitions editor of fiction. Neil Cochrane’s The Story of the Hundred Promises, forthcoming in October, and A Girl Called Rumi by Ari Honarvar are two Forest Ave titles that combine literary language with magical undercurrents. I’ve always been a fantasy reader, but I had put that piece of me aside when I began studying fiction and trying to write a big, contemporary novel. I still read and publish contemporary literary fiction, but my taste leans toward the playfully imaginative these days.

I read a lot of nonfiction titles while researching music boxes and the nineteenth century, but as for a longer-reaching change, I have definitely been drawn to more fantasy and genre-blending books since adding magic to this novel. Not just as a reader but as an acquisitions editor of fiction. Neil Cochrane’s The Story of the Hundred Promises, forthcoming in October, and A Girl Called Rumi by Ari Honarvar are two Forest Ave titles that combine literary language with magical undercurrents. I’ve always been a fantasy reader, but I had put that piece of me aside when I began studying fiction and trying to write a big, contemporary novel. I still read and publish contemporary literary fiction, but my taste leans toward the playfully imaginative these days.

Give the Laura who was at the beginning of Singing Lessons some advice, and give the Laura who is at the beginning of her next chapter a bit of advice.

Oh gosh. Keep going, no matter what. I stopped countless times with Singing Lessons, including getting lost midway through because of taking too much feedback and feeling muddled about what I wanted to say. So that’s the other piece: trust your instincts.

What do you, as the creator of this novel, want to be asked? What do you want writers and readers to know about you, or about your process?

It’s taken a long time to acknowledge my neurodivergence, even though I’ve always honored it on the page. I used to write characters who I thought were normal, but agents’ feedback suggested that they were strange, or immature, or not believable. I didn’t identify Henri or any of the other characters as neurodivergent in this story, but they are, and I love their weird, beautiful brains, just as I’ve grown to love my brain, for all its leaps and bounds and limitations.

For more about Laura and her novel, you can read this interview with Foreword This Week Editor-in-Chief Michelle Anne Schingler. You can also read Schingler’s review of the novel.

See Laura and Grace in conversation live at Browsers Books April 28 at 6:00 Pacific time with this registration link.