By the time he was twenty-nine, Charles Darwin had puzzled his way toward two-thirds of his theory of natural selection. He understood that plants and animals passed traits (hair color, say, or beak shape, or flower scent) down to their offspring. And he understood that those traits were not passed down perfectly. We resemble our parents, but we aren’t exact copies of them.

By the time he was twenty-nine, Charles Darwin had puzzled his way toward two-thirds of his theory of natural selection. He understood that plants and animals passed traits (hair color, say, or beak shape, or flower scent) down to their offspring. And he understood that those traits were not passed down perfectly. We resemble our parents, but we aren’t exact copies of them.

But he knew he was missing something, a third element, from his equation.

One afternoon in 1838, “for amusement” as he would later write in his autobiography, young Darwin picked up a forty year-old book by Thomas Malthus called An Essay on the Principle of Population. In it Malthus argues that populations grow geometrically while resources grow arithmetically. Given enough time, Malthus said, populations always outstrip food supplies.

One can almost imagine a light bulb illuminating inside Darwin’s head. “It at once struck me,” he wrote, “that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved and unfavourable ones to be destroyed.”[1]

Offspring with enough advantageous variations (we now call them mutations) get to make babies. Offspring with variations that prevent them from thriving don’t. Darwin had found his third element: “the grand crush of population.”

What I hope stands out from that little story is this: one day Charles Darwin picked up a book for fun and it helped him unlock one of the most significant ideas in the history of ideas.

For centuries we Westerners have been trying to draw clear lines between work and play, constructing a moral hierarchy that elevates one activity (work) above all others (not-working). As recently as 2015, American kindergarteners were doing 25 minutes of homework a night.[2] By the time most of us get our first jobs, we’re steeped in the paradigm of being on the clock or off it. Get cracking, we say. Take the bull by the horns, keep your nose to the grindstone, go the extra mile.

How many times in the past year have you seen a television commercial in which two handsome retirees in linen walk in slow-motion across a beach? The message is always the same: keep grinding for a little longer, and eventually, if you work long and hard enough, and purchase the right products, in the last years before your knees fall apart, you might finally get to go for a walk.

One day in 2014, just after the hardcover release of my novel All the Light We Cannot See, I drifted among the shelves of The Elliot Bay Book Company in Seattle. I had twenty minutes to kill before doing a book event, and for no particular reason I picked up 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West, by Roger Crowley.

One day in 2014, just after the hardcover release of my novel All the Light We Cannot See, I drifted among the shelves of The Elliot Bay Book Company in Seattle. I had twenty minutes to kill before doing a book event, and for no particular reason I picked up 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West, by Roger Crowley.

I read a few sentences, bought the book, carried it back to my hotel room after the event, and began to read.

I had been messing around with a piece of fiction set in outer space, and another piece set inside a walled city that I thought might be Constantinople. Did I think those projects were going to “go anywhere”? Were they going to “work out”? I had no idea: I was just playing around.

But as I read Crowley’s account of the 1453 siege of Constantinople, I began to catch distant glimpses, like glimmers of light flashing miles away, of how I might interconnect my outer space story and my walled-city story.

Seven years later, I’d written a novel called Cloud Cuckoo Land. A third of it takes place in Constantinople around the year 1453. Though a reviewer might call it part of “my work,” and though I spent many long days “working” on that book—days when I worried that the architecture of it would never hold up—the actual writing never really felt like work.

It was mostly play. Rich, hard, weird, complex play. And I might never have written this book at all if I hadn’t made time one evening to let my curiosity lead me through the aisles of an independent bookstore.

For me, the lesson of Darwin reading Malthus has always been: stay open. Stay open-minded, stay open-hearted. Amusement can be work and work can be amusement and true learning is always more play than it is labor.

It’s by entering the marvelous land of serendipity—by going for a walk between the shelves—that we find the things we didn’t know we needed. I’ll be forever grateful to bookshops like Elliot Bay—and every other of the 150 independent bookshops glowing all around the Pacific Northwest—for allowing us readers some space to drift between the aisles of work and play.

[1] (28 September 1838: from Darwin’s Autobiography).

[2] https://www.cnn.com/2015/08/12/health/homework-elementary-school-study/index.html

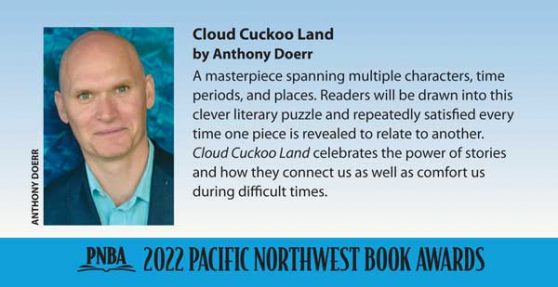

Celebrate Anthony Doerr and the other winners of 2022 Pacific Northwest Book Awards with the virtual event on Zoom Feb 8, 2022 at 6:00 PM Pacific Time. REGISTER NOW.

NWbooklovers posts original essays from this year’s award winners as featured posts in January and February. You can enjoy essays from past winners of the PNBA Book Award in our archive. Did you know that Anthony Doerr won a 2015 PNBA Book Award and the Pulitzer for All the Light We Cannot See? You can read his 2015 essay here.

It was while transcribing family letters from WWII that I came across and read All the Light…and I appreciate Doerr’s writing style and this essay, especially having grown up under the counter of a local bookstore in Idaho.

Yes, Harvard historian Stephen Jay Gould also wrote about Darwin’s wide reading in “Darwin and the Middle Road.”