Posted in Publishers Weekly Children’s Bookshelf newsletter May 7, 2019

Posted in Publishers Weekly Children’s Bookshelf newsletter May 7, 2019

by Emma Nichols, bookseller at Elliott Bay Book Company, Seattle, WA

When I first started in bookselling, parents often balked at my comics recommendations. They wanted their kids to read “real books.” Five years later, a lot has changed: I’m still recommending comics and kids are still reading them, but parents are finally coming around to accepting them. This is evident in the way people talk about comics: their legitimacy is no longer the main argument. But comics are still being challenged over content that has been taken out of context or misunderstood.

I recently participated in a panel at Emerald City Comic Con in Seattle, sponsored by the CBC Graphic Novel Committee, where the other panelists (Daniel Barnes and DJ Kirkland, creators of The Black Mage; Kristen Gudsnuk, creator of Making Friends; and moderator Besty Gomez, coordinator of Banned Books Week) and I discussed how comics can be used to portray tough topics and how the industry can prevent or fight against the challenges that comics still face. The audience was made up of teachers and librarians, adults who, like me, are on the front lines, defending comics as a source of delight and development. Defense is becoming less and less necessary, but I still carry a couple of arguments in my arsenal.

I recently participated in a panel at Emerald City Comic Con in Seattle, sponsored by the CBC Graphic Novel Committee, where the other panelists (Daniel Barnes and DJ Kirkland, creators of The Black Mage; Kristen Gudsnuk, creator of Making Friends; and moderator Besty Gomez, coordinator of Banned Books Week) and I discussed how comics can be used to portray tough topics and how the industry can prevent or fight against the challenges that comics still face. The audience was made up of teachers and librarians, adults who, like me, are on the front lines, defending comics as a source of delight and development. Defense is becoming less and less necessary, but I still carry a couple of arguments in my arsenal.

Argument #1: Comics are approachable and kids want to read them. If your kids wanted to read the manual for your Ford Explorer, would you discourage them? Reading is reading is reading. For the reluctant reader, comics can be easier to grasp and more fun to read than text-only books.

Argument #2: Comics are more complex than prose books. I know this seems counterintuitive to argument #1, but it’s true; they demand engagement on both a visual and textual level.

Our panel covered more interesting arguments. Like, why should I give my kid a comic that is littered with the n-word? In March by Sen. John Lewis, the n-word is never defined; its painful meaning is obvious in the leering faces the word emerges from. A chapter book would require far more words to convey the emotion, the racism, and the hope that Lewis manages to capture in a single panel.

Our panel covered more interesting arguments. Like, why should I give my kid a comic that is littered with the n-word? In March by Sen. John Lewis, the n-word is never defined; its painful meaning is obvious in the leering faces the word emerges from. A chapter book would require far more words to convey the emotion, the racism, and the hope that Lewis manages to capture in a single panel.

Another argument from a parent could be, “Why should I give my daughter a comic where a teenager is traumatized by rape?” When I was a teenager, Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson taught me important lessons about speaking up for and valuing myself. Today, a reluctant reader, who may be intimidated by the novel, can learn those lessons by reading the graphic adaptation of Anderson’s novel while also enjoying the stark and lovely art of Emily Carroll.

We discussed the clarity of emotions that can be conveyed when pictures and words are employed simultaneously, the way that struggling readers may improve their understanding of difficult situations with visual cues, and the way that stories can feel more real and be more relatable when a face is attached to them. March gives a tangible, human element to a historical event that may otherwise feel unknowable.

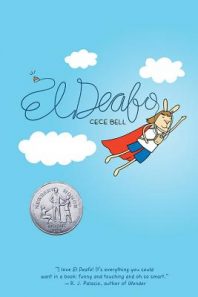

Comics can take risks; there are more elements to experiment with and manipulate: not just words but lines, colors, panel structures. Comics started as a lighthearted medium—mostly about action and humor; we discussed how these beginnings allowed comics to approach more difficult topics at a kind of slant. A comic about being deaf can also be a comic about having superpowers, as is the case with Newbery Honor– and Eisner Award–winning El Deafo by Cece Bell.

Comics can take risks; there are more elements to experiment with and manipulate: not just words but lines, colors, panel structures. Comics started as a lighthearted medium—mostly about action and humor; we discussed how these beginnings allowed comics to approach more difficult topics at a kind of slant. A comic about being deaf can also be a comic about having superpowers, as is the case with Newbery Honor– and Eisner Award–winning El Deafo by Cece Bell.

A downside of comics, at least for those teaching them, is that they are often challenged by parents and guardians, as a panel divorced from its context is easy to misunderstand. The panelists agreed that when a controversy arises it should be approached deliberately and directly. If someone finds a fleeting mention of abortion problematic, booksellers should discuss how the topic is broached and encourage questions and conversations. When people feel that their concerns are understood and addressed, they’re often more comfortable engaging with tough content.

Books don’t exist solely for entertainment; they make us think, empathize, and consider the world around us from all angles. Hopefully our kids won’t have to deal with bullies, racism, abuse, or war—but probably they will. Books in general show us that these seemingly insurmountable obstacles can be overcome. Comics show that to kids in a visual, tangible way.

Emma Nichols is a manager at Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle. She also writes the All the Books I’ll Never Read newsletter and cohosts the Drunk Booksellers podcast.