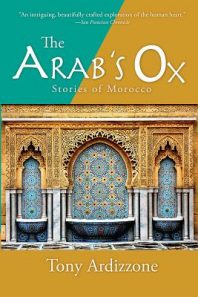

Tony Ardizzone was interviewed by Walter Wetherell in celebration of the 25th anniversary edition of Tony’s collection of stories, The Arab’s Ox: Stories of Morocco (originally published as “Larabi’s Ox”), on sale February 2018. The book was awarded the Chicago Foundation for Literature Award for Fiction, a Pushcart Prize, a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Milkweed Editions National Fiction Prize, selected by Gloria Naylor.

Tony Ardizzone was interviewed by Walter Wetherell in celebration of the 25th anniversary edition of Tony’s collection of stories, The Arab’s Ox: Stories of Morocco (originally published as “Larabi’s Ox”), on sale February 2018. The book was awarded the Chicago Foundation for Literature Award for Fiction, a Pushcart Prize, a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Milkweed Editions National Fiction Prize, selected by Gloria Naylor.

Walter Wetherell: Great to talk with you again, Tony. Congratulations on the 25th anniversary edition of your Moroccan stories. The San Francisco Chronicle said your book was “intriguing, beautiful crafted,” and the Chicago Tribune called it “travel literature of a high order.” That’s pretty lofty praise. How do you think the new edition is going to resonate with readers today?

Tony Ardizzone: Thanks, Walter. The timing of the book’s re-release seems right. Both the Arab world and the religion of Islam are in the news everyday. The Arab’s Ox will give readers a sense of not only what’s it like to travel in an Arab country but also what it’s like to live there. I hope it gives readers what they want in fiction—an engaging experience that takes them to a place they’ve never been.

Tony Adrizzone

WW: Let’s talk about the book’s basic structure. It begins with an accident involving an ox and a bus?

TA: A shuttle from the Casablanca airport on its way to the capital city of Rabat hits and kills an ox that has wandered out onto the road. Three of the book’s main characters are on the bus—Henry Goodson, Sarah Rosen, and Peter Corvino. All of them have come to Morocco for different reasons. They all need something.

WW: And the three don’t interact.

TA: Henry sees the other two but once the bus arrives in Rabat the three go their separate ways. It’s like a tree and its limbs. The accident with the bus and ox are the trunk, the characters the limbs that branch out into individual stories. Allowing the characters to go their separate ways lets me take the reader all over the country.

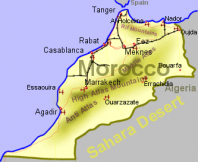

I gave each of the characters a particular area of Morocco to explore, and along the way they pick up other characters. Peter’s stories are set in Rabat, the capital city, and Casablanca. Henry’s storyline begins in Rabat, where he meets a university student, Ahmed Ousaid, who eventually takes Henry to his Berber home in Ouarzazate and later to the edge of the Sahara. Sarah travels to Fez, where she meets Rosemary Fisher, an expatriate. Together, the two women travel to romantic Marrakesh.

I gave each of the characters a particular area of Morocco to explore, and along the way they pick up other characters. Peter’s stories are set in Rabat, the capital city, and Casablanca. Henry’s storyline begins in Rabat, where he meets a university student, Ahmed Ousaid, who eventually takes Henry to his Berber home in Ouarzazate and later to the edge of the Sahara. Sarah travels to Fez, where she meets Rosemary Fisher, an expatriate. Together, the two women travel to romantic Marrakesh.

WW: The Review of Contemporary Literature called the book’s setting “a fourth character.” What do you think they meant by that?

TA: I took that as a high compliment. Morocco is too beautiful and intricate not to be described. And since Morocco stands separate from the characters, I wanted the descriptions of Moroccan settings to stand alone, too. For me, Moroccan culture was overwhelming — rich, intoxicating. Living there, I was constantly challenged. So I passed some of these experiences and sights to the book’s characters. Their understanding of Morocco is essential to their development.

TA: I took that as a high compliment. Morocco is too beautiful and intricate not to be described. And since Morocco stands separate from the characters, I wanted the descriptions of Moroccan settings to stand alone, too. For me, Moroccan culture was overwhelming — rich, intoxicating. Living there, I was constantly challenged. So I passed some of these experiences and sights to the book’s characters. Their understanding of Morocco is essential to their development.

One of my Moroccan friends said my book was a like a photo album that captured a particular place at a specific time.

WW: Let’s talk about a few of the book’s themes. Sarah’s decision to come to Morocco by herself, and later to travel with Rosemary, raises the plight of women traveling not in the company of men.

TA: Sarah encounters problems traveling alone, as a woman, at every turn. She has difficulties in Rabat, and a really frightening experience in the old medina in Fez. The ancient Fez medina is built like a maze. You need a guide if you go there. For reasons that I won’t explain here, Sarah’s guide abandons her and she sees a face of Morocco that’s usually hidden.

WW: What about clashes between Moroccan and Western perspectives?

TA: This thread is carried out by Henry and Ahmed. Each is the focal character of two stories. Ahmed admires Americans, to a point, and wants to learn their language and idioms and to earn a few of the dirhams jingling in their pockets. Henry has led a lonely life. He’s eager for connection as he’s forced to come to terms with the reality that he’s dying. Their ideas about the world clash as they travel over the High Atlas mountains and visit Ahmed’s family home.

WW: The book also presents the intersections of world religions.

TA: Peter is Roman Catholic and sometimes says the rosary to help himself fall asleep. Sarah is Jewish. Of course Ahmed is Muslim and often helps Henry, an agnostic, understand what a foreigner can or cannot do in this country.

WW: The Arab’s Ox gives a vivid picture of poverty and disability.

TA: Peter carries this theme. During my first stay in Morocco I was struck by the beggars, particularly the women begging on the curb of a street while breast-feeding an infant. Peter is told by a bitter Frenchman on the flight from JFK to Casablanca that there is no real poverty in Morocco, that the beggars are a sham and he should totally ignore them, but Peter comes to see that their poverty is real. His response to their needs gives him a way to live and thrive in the country.

WW: You mention a Frenchman. Is he another returning character in The Arab’s Ox?

Tony: The Frenchman makes two appearances in Peter’s first story, “The Beggars.” Morocco was ruled by France and only gained its independence, peacefully I might add, in 1956. While I met many people from France who lived and worked in Morocco and held Morocco in the highest regard, I also observed several instances of outright insult and racism, mainly by French tourists.

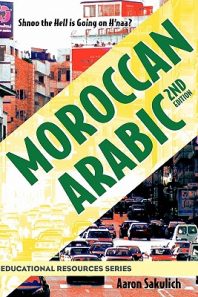

My French is very bad. I know a little Spanish and some Italian and came to rely on these languages, along with English and the bits of Moroccan Arabic I was learning along the way. It ended up that not speaking French was to my advantage because it was the language of the colonizer, even though Morocco had been a French protectorate rather than a colony. Ultimately, I just kept my mouth shut. Good advice for a writer. I learned by seeing, by paying close attention. I was free of the demands of language and the complication of thinking of the next thing to say.

My French is very bad. I know a little Spanish and some Italian and came to rely on these languages, along with English and the bits of Moroccan Arabic I was learning along the way. It ended up that not speaking French was to my advantage because it was the language of the colonizer, even though Morocco had been a French protectorate rather than a colony. Ultimately, I just kept my mouth shut. Good advice for a writer. I learned by seeing, by paying close attention. I was free of the demands of language and the complication of thinking of the next thing to say.

Walter: What can a reader relate to or learn by reading your book?

Tony: I hope the reader will come away with the affirmation that we’re all human, worthy of love and respect, despite where we come from or what we believe. I also hope the reader will experience a sense of Moroccan culture as well as a greater understanding of Islam, a religion that I came to deeply respect. Finally, it would be great if it made them want to travel to Morocco, or if they’ve already been there I hope the book revives their memories.

Morocco is an exquisite country. There’s no other place in the world like it.

Tony Adrizzone is a writer, teacher, and editor. He has been awarded two Individual Artist Fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, the Milkweed Editions National Fiction Prize, the Chicago Foundation for Literature Award for Fiction sponsored by the Friends of Literature, the Virginia Prize for Fiction, the Pushcart Prize, the Lawrence Foundation Award, the Bruno Arcudi Literature Prize, the Prairie Schooner Readers’ Choice Award, the Black Warrior Review Literary Award in Fiction, and the Cream City Review Editors’ Award in Nonfiction. Adrizzone lives in Portland, OR. See his website for more information or to contact him.

W. D. Wetherell is the prize-winning author of two dozen books, including the novels Chekhov’s Sister and A Century of November, and the story collections The Man Who Loved Levittown and Where We Live, due out in the autumn of 2018. His book on the forgotten literature of World War One, Where Wars Go to Die, appeared in 2016, and his reviews and criticism have appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, and many other publications.