The house where my father grew up is immortalized on an old Egyptian banknote. It’s the 25 or 50 piastre bill, I think, though I haven’t seen one since I was a child and they’ve been redesigned since then. The old bill, if memory serves me correctly, features a drawing of a narrow alleyway in El Hussein, one of Cairo’s oldest neighborhoods. In the shadow of the ancient mosque, above the silversmith stalls, there’s a wood-shuttered window my father says was his.

The house where my father grew up is immortalized on an old Egyptian banknote. It’s the 25 or 50 piastre bill, I think, though I haven’t seen one since I was a child and they’ve been redesigned since then. The old bill, if memory serves me correctly, features a drawing of a narrow alleyway in El Hussein, one of Cairo’s oldest neighborhoods. In the shadow of the ancient mosque, above the silversmith stalls, there’s a wood-shuttered window my father says was his.

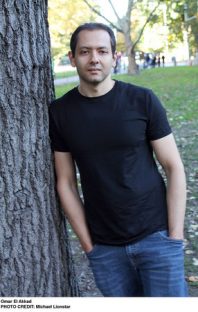

My father was 28 years old when I was born. He lived another 28 years, I knew him only for the back half of his life. These were transient years, a time he spent away from the country of his birth and the culture in which, during his formative years, he marinated.

By the time I was born in the early ’80s, the ugly business of reclaiming identity in the aftermath of colonialism had left much of the Middle East and North Africa hopelessly dysfunctional. Egypt, like so many of its neighbors, was under pseudo-dictatorial rule: The line between military and civilian government seemed nonexistent. An emergency curfew imposed after President Anwar Sadat’s assassination in 1981 quickly became a fixture of daily life. The economy was in tatters.

Unable to find decent employment in his homeland, my father took a job as a junior accountant in a hotel in Qatar, at the time an obscure peninsula jutting out the eastern edge of Saudi Arabia. Today Qatar is perhaps the richest country on earth, but back in the mid-’80s it was relatively unknown, a nation barely older than some of my relatives, and its residents had only just begun to exploit the great reserves of oil and natural gas that lay beneath the sand. There was money to be had, a chance for my father to provide a decent living for his family. He took it. Not long after, my mother and I joined him. I was five years old. Since that day, I have been a migrant.

The word meanders, its meaning a function of the intent with which it is said. The novelist Mohsin Hamid wrote that we are all migrants: we migrate through time. This is true, but we are made to board very different carriages.

In Qatar migrants were the majority. We flooded the oil-rich state and, in that very limited way governed by race and class and ethnicity, we intermingled. Qatari citizenship is almost impossible to obtain by non-hereditary means, and so we understood from the beginning that ours was to be a state of permanent guesthood. We did not belong to this place and it did not belong to us.

The hardcover

Every migrant carries a designation, a label befitting the extent of their powerlessness. In Qatar, we rarely saw refugees, the untouchables of the migrant class. Sometimes the word was used to describe Palestinians, descendants of those who had been forced to flee their land and whose history had been taken from them and transformed into a beast of politics. Sometimes the word was used to describe Kuwaitis who left their homes after the first Gulf War. But in reality, there were effectively no refugees in Qatar, no room for those whose very existence betrays a failure of our collective humanity – rich nations can insulate themselves from such unpleasantness.

There were, however, plenty of economic migrants. They came from India and Pakistan and Bangladesh and the Philippines and they made up the bulk of the population in a country where almost everyone came from somewhere else. They paved the roads and built the skyscrapers and waited hand and foot on the privileged classes and for their efforts were rewarded with working conditions indistinguishable from indentured servitude. Still, the wages they could earn here were slightly higher than the pay back home, so they came, and they suffered, and every month they sent a few dollars back to the families they left behind. In reality, these were also refugees of a kind, refugees from the grand and unsparing whims of a centuries-long imperialism and its myriad economic aftereffects, refugees from history. I doubt a single one of the men and women who came to places like Qatar – to toil in the searing heat, to be treated by their employers as subhuman – would have chosen to do so if the alternative was anything other than crushing poverty (or worse) back home. As the Somali-British poet Warsan Shire wrote, “no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.”

But in Qatar I also came to know expats, migration’s regal class. The term was reserved, almost exclusively, for the white westerners who came to Qatar in search of better salaries, less competition and a vastly more comfortable lifestyle. Every foreigner in Qatar wanted to ascend to the rank of expat, a migrant whose migration is never questioned.

I lived 11 years in Qatar. Many of the friends I grew up with never left. They got married and had children and built their whole lives atop soil that would never truly accept their roots. They had no other choice, they’d been there too long, the places from which they’d come were alien now, distant repositories of memory and genealogy and little else. They belonged to nowhere.

I lived 11 years in Qatar. Many of the friends I grew up with never left. They got married and had children and built their whole lives atop soil that would never truly accept their roots. They had no other choice, they’d been there too long, the places from which they’d come were alien now, distant repositories of memory and genealogy and little else. They belonged to nowhere.

More than any nationality or ethnicity or religion, this is the tribe to which I feel strongest attachment: the tribe of the unrooted.

In the last year, since my debut novel was published, I’ve fielded many questions about why and what I choose to write. I write about the absence of place. Growing up, my literary heroes were writers so firmly planted in the land they wrote about that they seemed not to write their stories but exhale them: Toni Morrison, William Faulkner, Naguib Mahfouz. To this day I envy their sense of rootedness (which permeates their work, even when they write, so brilliantly and with such meticulous care, about the feeling of being unrooted). I envy the mastery with which they put place to paper. I want for their talent, I want for their fluency.

But what my favorite writers saw clearly in stillness, I perceive through the lens of movement. The places in which I set my fiction are Frankensteins – hybrids of the many countries and cultures that shaped my view of the world. My fiction is a migrant.

In my mind, American War is not a book about America. It’s a novel about what happens when people are violently uprooted, stripped of place and stripped of agency. The country in which the story takes place is in almost every way a country becoming nowhere.

It has taken me a long time – the entirety of my adult life – to understand that this is what compels me to write fiction. I write about the absence of place. I write about what it means to not belong.

Every few years, whenever I go back to Egypt, I visit my father’s grave, and the neighborhood he once called home. I walk around El Hussein, I pray in the beautiful old mosque, the star around which the whole neighborhood spins. I know it’s not the same for me as it was for him, it never will be – the silversmiths cater mostly to the tourists now, the coffee shops where the poets used to hold court are either gone or irreversibly changed. Time is a barbed abyss and to come to a place like this is to feel most intimately the endless falling.

But despite all things, I still sense here a hint of the past that made me. In this country I left at the age of five, whose government I despise and whose streets I can barely navigate, there exists a history of which I am a part and that will outlive me, the way soil outlives what’s planted in it, the way stories outlive their tellers. The old house on the banknote, which in my life exists only as a function of inherited memory, can never cease to be.

I can’t ever be of this place, or any place, the way my father was. Still, I feel obliged to try.

The plaque for the 2018 PNBA Book Award for American War will be presented to Omar El Akkad at Broadway Books of Portland, OR on Tuesday, March 12th, time TBD. nwbooklovers has posted original essays from this year’s award winners on Fridays in January and February. You can enjoy essays from past winners of the PNBA Book Award in our archive.