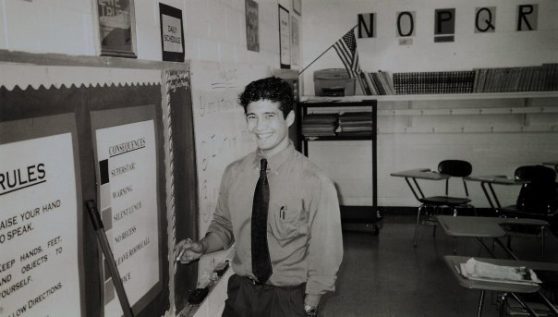

When Michael Copperman left Stanford University for the Mississippi Delta in 2002, he imagined he would lift underprivileged children from the narrow horizons of rural poverty. Well-meaning but naïve, the Asian American from the West Coast soon lost his bearings in a world divided between black and white. He had no idea how to manage a classroom or help children navigate the considerable challenges they faced. In trying to help students, he often found he couldn’t afford to give what they required―sometimes, with heartbreaking consequences. His desperate efforts to save child after child were misguided but sincere. He offered children the best invitations to success he could manage. But he still felt like an outsider who was failing the children and himself.

Copperman in his classroom in 2002

Teach For America has for a decade been the nation’s largest employer of recent college graduates but has come under increasing criticism in recent years even as it has grown exponentially. This memoir considers the distance between the idealism of the organization’s creed that “One day, all children will have the opportunity to attain an excellent education” and what it actually means to teach in America’s poorest and most troubled public schools.

Copperman’s memoir vividly captures his disorientation in the divided world of the Delta, even as the author marvels at the wit and resilience of the children in his classroom. To them, he is at once an authority figure and a stranger minority than even they are―a lone Asian, an outsider among outsiders. His journey is of great relevance to teachers, administrators, and parents longing for quality education in America. His frank story shows that the solutions for impoverished schools are far from simple.

Independent Publicist Erin Kottke conducts a Q & A with Michael Copperman, author of Teacher: Two Years in the Mississippi Delta

Independent Publicist Erin Kottke conducts a Q & A with Michael Copperman, author of Teacher: Two Years in the Mississippi Delta

EK: You describe yourself as “a mixed-race Japanese-Hawaiian Russo-Polish Jew who could be Asian, Hispanic, perhaps Eskimo or Greek or some other unknown miscegenation.” You were the first person of Asian descent that some of the children you taught at the all-black school had ever met in their lives—indeed, there were adults in town who had never met someone who wasn’t black or white. How did your “outsider” status affect your experience in the Delta?

MC: Growing up interracial in Oregon, one of the whitest states in the nation, I was often the only minority, and was at times isolated, ostracized, and bullied— an outsider who didn’t belong. Coming in a middle-shade and encountering the Delta’s black-white binary, burdened as it was by hierarchy and history, confirmed my outsiderness. To the kids in the black public schools, I was often the first not-white person they’d ever spoken to, their exclamations audible: “Oooweee, there that China-man go. Do he know the kung fu?”

Many whites, on the other hand (who still own most of the wealth and land in the Delta), would tell me how they thought of me as being “near white,” before saying something racist about Asians; when they heard I taught in the public schools, they would often proffer sympathy or express horror at my “having to teach those monsters” or “that kind.” I came to see my difference as strangely neutral there—the misunderstandings of black kids, and even black adults, were relatively harmless, and as for whites, the damage their stereotypes or ignorance could do to me was insubstantial before the ugliness of racism directed against children.

EK: You say that Promise, Mississippi is “the heart of the Mississippi River Delta, the poorest and blackest part of the poorest and blackest state in the nation.” The school district there is deeply segregated and the achievement gap between white and black students is massive. Is it overly idealistic to think that such huge disparities can be overcome through organizations like Teach For America?

MC: The achievement gap is rooted in historical race and class inequality; it cannot be unmade by any one organization. Teach For America has claimed to be able to reform the system, and has at times been elitist and guilty of overreach. Yet if you look at the state of Mississippi, you do see long-term impacts from TFA’s presence, especially in the longer-term commitments of many alums in the state. I am critical of the organization, but I believe in the justice of its mission—which is to say, I remain committed to children who had no choices about the circumstances and opportunities they were born into. The public education system, despite its many failings and dysfunctions, is worth our investment.

EK: In your new book, Teacher, you say that “I have begun to forgive myself for having failed [the students].” How did you fail them, and how have you—and they—moved past that?

MC: I failed the students in more ways than I can name: through ignorance and inexperience, through lack of preparation, naiveté, assumption, through poor instruction, bad management, ego and anger and error. I thought for a long time that I failed them by not being able to remake the world or the system—I was an overachiever from a generation told I could “be the change I wanted to see.” Instead, I was changed by the kids, who I have carried with me, in their voices and stories, in their innocence and aspiration and merit. I set out to atone, and became an educator; those students made me who I am.

Of course, it was hubris to think I could lift them from circumstances and history in two brief years. A few kids are in college now, and some are just finishing and graduating, and some never graduated high school, or did, but never left the community where I taught. I try to follow their lives because I care about them.

MICHAEL COPPERMAN has taught low-income, first-generation students of diverse backgrounds writing at the University of Oregon for a decade. His work has appeared in the Sun, the Oxford-American, Guernica, Creative Nonfiction, and Salon, and garnered fellowships and awards from the Munster Literature Center, the Oregon Arts Commission, Literary Arts, and Breadloaf Writer’s Conference. He lives in Eugene, Oregon.