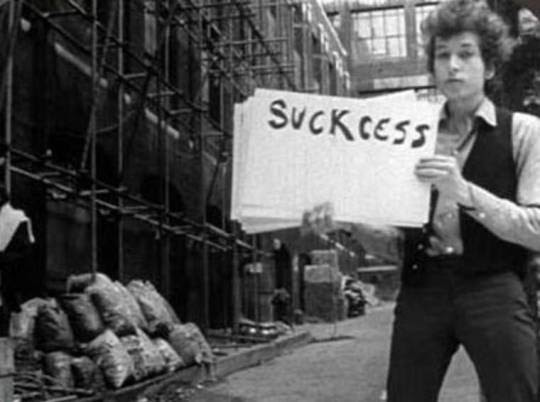

2016 was already a pretty weird year, but last week a few people in Stockholm found a way to take it over the top. As you’ve probably heard by now, the Swedish Academy awarded Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature, citing him for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Most celebrated the selection (Rolling Stone’s reaction is a characteristic example) but a substantial minority of onlookers questioned it, including Irvine Welsh, who tweeted the following:

I’m a Dylan fan, but this is an ill conceived nostalgia award wrenched from the rancid prostates of senile, gibbering hippies.

I wouldn’t go that far, but the choice didn’t sit right with me, either.

Let me stipulate up front that I’m not knocking Dylan as an artist. His output is vast and varied, and much of it is brilliant. His lyrics have influenced generations of songwriters and without doubt can be considered as poetry of a high order, as scholar Christopher Ricks does so well in his book Dylan’s Visions of Sin. To borrow from the witty John Hodgman, a veritable Algonquin Round Table unto himself, my “reaction was not ‘HOW DARE THEY!?’ It was more a confused, slightly skeptical ‘What? Really?’” It’s not that Dylan’s win was a mistake, more that it was beside the point.

There are two main reasons I say this. The first has to do with what we mean when we talk about “literature,” and Stephen Metcalf in Slate summarized my feelings on the subject quite well when he wrote:

The objection here hinges in the definition of the word literature. You wouldn’t give the literary prize to an economist or a political saint. You shouldn’t give it to Bob Dylan.

My thinking goes as follows, and who knows, I’m probably wrong. But the distinctive thing about literature is that it involves reading silently to oneself. Silence and solitude are inextricably a part of reading, and reading is the exclusive vehicle for literature …

Reading silently, a kind of crossroads is formed. Your voice, on the page, becomes my voice, in my head. In reading, the mind is made separate from the mechanistic and perspicuous world, and a self is formed that is not precisely in or of that world. In reading, you experience that rarest loneliness, a loneliness that reminds you: You exist.

Ah, you say, but what about the handful of playwrights who’ve been handed Nobel Prizes? Didn’t they write for public performance? Well, at least in the cases of Shaw and Beckett, they wrote as much for the page as for the stage. Even discounting them to look at Pinter and Fo and whichever other dramatists you want to name, they wrote for others to perform. That’s not the kind of work that the Swedish Academy honored last week. Quoting Hodgman again:

Songs are not “poems set to music.” They are lyrics and music written together, to complement and to create a whole effect that may be greater than either part alone. Additionally, and thanks to Dylan, they are entwined with performance–in the case of Dylan, a very personal and singular style of performance.

We’ve just seen the definition of literature expand in a way that seems unnecessary. It’s not as though songwriters lack recognition and reward for their work, especially not one like Bob Dylan, who’s sold kajillions of records and been acclaimed worldwide for a half-century. As I mentioned before, he’s already a hugely significant artist, probably more so than many of his fellow literary laureates. This prize doesn’t elevate him further; as Leonard Cohen commented, it’s “like pinning a medal on Mount Everest for being the highest mountain.” The biggest problem with the Nobel Prize in Literature (other than its shameful record of ignoring women and people of color) is that it annually insults many deserving writers by overlooking them, Woolf, Joyce, Borges, and Proust being only the most famous examples. In trying to honor this year’s recipient, the Swedish Academy has merely added Cohen, Tom Waits, Carole King, Cole Porter, and Stephen Sondheim to that list of also-rans.

Which brings me to my second objection, the long line of authors who’ve been knocking on the Nobel’s door for years without being admitted. Their chances just went from slim to slimmer. By the time the academy’s gaze turns to North America again, it will probably be far too late for the likes of DeLillo, Roth, Atwood, McCarthy, or Oates. Even more hard hit are the many equally talented but lesser-known writers from around the world, the kinds of people who inspire a collective “Huh?” when their names are read out in Stockholm. Some complain about these allegedly obscure selections, but they’re what I’ve always thought the prize was all about. They’re the ones who could use the recognition, and, frankly, the million bucks that the Nobel brings with it.

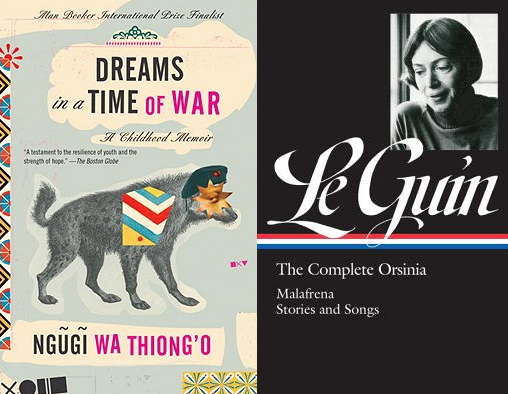

I’m thinking now of deserving could-be laureates like Kenya’s Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Hungary’s László Krasznahorkai, China’s Can Xue, Syria’s Adonis, Croatia’s Dubravka Ugresic, and Estonia’s Doris Kareva. Or heck, if the Swedish Academy wants a populist choice, why not the Northwest’s own Ursula K. Le Guin? Honoring her contributions to speculative fiction would usefully expand the Nobel’s definition of literature in a way I don’t think Dylan’s selection does. While the world’s attention is focused on his song lyrics and his other writing, I hope it can spare some time for these other worthies. Since the man of the hour hasn’t even said yet whether he’ll be attending the ceremony, maybe they can sit at his empty table.

James Crossley can be found reading silently to himself and aloud to others when he’s not working at Island Books. Sometimes, he even sings.