When you stop to think, it’s odd to celebrate the day a person, however famous, shuffled off this mortal coil. Regardless, this April 23rd marks the 400th Deathiversary of one William Shakespeare, a writer of no little renown, and the whole world is throwing a party. There are any number of commemorative activities underway where I live, including productions of his plays in bars and backyards, but the centerpiece of the festivities is at the Seattle Central Library, where a rare copy of the First Folio, the 1623 book that established the bard’s dramatic canon, is on exhibit until April 17th.

When you stop to think, it’s odd to celebrate the day a person, however famous, shuffled off this mortal coil. Regardless, this April 23rd marks the 400th Deathiversary of one William Shakespeare, a writer of no little renown, and the whole world is throwing a party. There are any number of commemorative activities underway where I live, including productions of his plays in bars and backyards, but the centerpiece of the festivities is at the Seattle Central Library, where a rare copy of the First Folio, the 1623 book that established the bard’s dramatic canon, is on exhibit until April 17th.

As a current bookseller, former English major, and closet theater geek, I was triply obliged to make a pilgrimage to see this secular relic, so I headed downtown, free ticket in hand. I was neither wowed nor disappointed by the experience–I guess you’d say I was whelmed. In the end, the focus of all the excitement is simply a very old book in a glass box in a dimly-lit room on the eighth floor of an even bigger glass box.

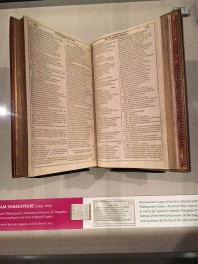

The First Folio: open to the “To be or not to be” speech from Hamlet

Of course, it’s pretty cool to be able to say that I’ve been in the presence of an actual First Folio, but I’m not even sure which book I saw. Of the 230 or so remaining copies (one more just turned up in Scotland) from the original edition of 750, the other Washington’s Folger Library owns more than 80, including the one that’s on loan to Seattle. Depending on the order of printing, condition, and the provenance of each individual book, they vary widely in importance and value; for security reasons, it won’t be revealed which one is in the Northwest until after it’s returned.

If that’s the kind of thing you wonder about as much as I do, pick up The Book of William by historian Paul Collins, which ably and engagingly covers all the necessary First Folio arcana. Or read The Millionaire and the Bard by Andrea Mays, about the wealthy industrialist, Henry Folger, who became the most obsessed Shakespeare collector on the planet and gave his name to the library that made this exhibition possible.

Costumes on display from the Seattle Shakespeare Company (a production of “The Merry Wives of Windsor”)

The peripheral displays there were as appealing as the Folio itself, providing a fairly comprehensive survey of a century of Seattle’s interest in the arts. Even when they were building a frontier town, local residents found time to take in a Shakespeare play. In this they had much in common with their fellow countrymen and -women, who have embraced the writer as a populist literary hero since before the Revolution. The history of that relationship can be traced in the Shakespeare in America anthology, edited by scholar James Shapiro.

He’s also the author of The Year of Lear, a perfect read for anyone who questions the relevance or accessibility of an author who’s been gone for 400 years. It tells of a middle-aged city dweller who’s struggling to get the job done in a nation riven by politics and threatened by bomb-crazed religious fanatics. Sounds a bit like 2016, but we’re speaking of 1606, and that working stiff happened to be producing King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra, all in a twelvemonth. That would be an impressive accomplishment even if those works had been completely forgotten, which of course they weren’t. More people love them now than when their creator was alive.

Shakespearean merch: Bring the Bard home, from the Friends of SPL gift shop.

Shakespeare’s ability to speak to contemporary audiences is almost unique, as Stephen Greenblatt, author of Will in the World, pointed out recently in the New York Review of Books:

Shakespeare’s greatest contemporary playwrights, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, both seem directly and personally present in their work in a way that Shakespeare does not … [He] seems to have felt no comparable desire to make himself known or to cling tenaciously to what he had brought forth …

Shakespeare’s works … continue to circulate precisely because they are so amenable to metamorphosis. They have left his world, passed into ours, and become part of us. And when we in turn have vanished, they will continue to exist, tinged perhaps in small ways by our own lives and fates, and will become part of others whom he could not have foreseen and whom we can barely imagine.

Further proof of this is the unabated flow of publication about his plays and how they influence modern life. In his time, women were not allowed to walk on stage, yet he wrote some of the richest female roles in history. See actor, director, and teacher Tina Packer’s Women of Will for more on that topic. He lived long before the Sexual Revolution occurred or was even imaginable, yet at least one young woman in the 21st century, Jillian Keenan, finds his work the most useful lens for understanding her own transgressive erotic life, and explains how this is so in her memoir Sex with Shakespeare: Here’s Much to Do with Pain, But More with Love.

Fiction writers also still look to him for inspiration. Take the fantasists behind Monstrous Little Voices, which creates a coherent magical world that combines the witches of Macbeth, Prospero’s spells, and the fairies of Midsummer’s Night with a realistic look at Renaissance wars and politics. Or author Andrea Chapin and her new novel of historical romance, The Tutor. Or dramatist Mike Bartlett, who has rendered the royal succession scandals of the near future into the Shakespearean-inflected verse of King Charles III, coming to the Northwest stage next season.

Better yet, go to the theater to see Shakespeare straight, or pick up a beautiful edition of his sonnets or his plays. Take your time–there’ll be another party and another reason to celebrate him no matter when you get around to it.

James Crossley is a bookseller and blogger at Island Books on Mercer Island. He could read (and talk with you) about Shakespeare for forever and a day, but he also understands that brevity is the soul of wit.