Shann Ray Ferch may just be the most peaceful man I’ve ever met. I don’t know the Dali Lama and I totally missed seeing the Pope during his USA Tour 2015, but Shann Ray will serve as a satisfactory, calm-centered substitute for those two gentlemen. Shann the writer is every bit as open-hearted and gracious as Shann the man. In his short fiction (American Masculine) and poetry (Balefire), we find peace, forgiveness and humility laid alongside sentences that shatter us with descriptions of violence. Shann is working on a new image of the West–one where grace and brutality co-exist.

Shann Ray Ferch may just be the most peaceful man I’ve ever met. I don’t know the Dali Lama and I totally missed seeing the Pope during his USA Tour 2015, but Shann Ray will serve as a satisfactory, calm-centered substitute for those two gentlemen. Shann the writer is every bit as open-hearted and gracious as Shann the man. In his short fiction (American Masculine) and poetry (Balefire), we find peace, forgiveness and humility laid alongside sentences that shatter us with descriptions of violence. Shann is working on a new image of the West–one where grace and brutality co-exist.

Unbridled Books publishes his debut novel, American Copper, this month and it is every bit as beautiful and breathtaking as the stories in American Masculine. American Copper has a huge timesweep, from the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 to the years just before World War II, but it is, at heart, an intimate novel. It traces the lives of three individuals: Evelynn Lowry, daughter of a copper baron who practically owns the city of Butte, Montana; William Black Kettle, a Cheyenne team roper; and a great bear of a man named Middie (aka Zion) who ends up working as a bouncer on a passenger train. Middie was also seen in American Masculine’s story “The Great Divide,” a narrative that Shann skillfully weaves into American Copper. Shann and I recently conversed, via email, from our homes in Spokane and Butte, respectively.

–David Abrams, author of Fobbit and editor of The Quivering Pen blog

David Abrams (DA): Let’s begin with the genesis of American Copper. Readers of American Masculine will pretty quickly recognize the character named Middie from one of my favorite stories, “The Great Divide.” When you were working on that story, did you always know you’d do more with Middie?

David Abrams (DA): Let’s begin with the genesis of American Copper. Readers of American Masculine will pretty quickly recognize the character named Middie from one of my favorite stories, “The Great Divide.” When you were working on that story, did you always know you’d do more with Middie?

Shann Ray (SR): Early on, I felt Middie’s story could be expanded. His loneliness and his goodness are a part of his fiber. He is desolate, yet he desires to be more whole, and more capable of redemptive connection to others. He straddles, largely unsuccessfully, both white and Cheyenne cultures. The other primary characters–Evelynne Lowry the copper baron’s daughter, and William Black Kettle, a descendant of Cheyenne peace chiefs–are also largely unsuccessful in their attempts to bridge Cheyenne and white cultures. Yet they embody the hope to heal the atrocities of the past.

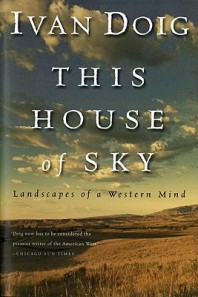

With American Copper I wanted to write a love song to Montana—to Montana’s people, all of Montana’s people, and to Montana’s wilderness. Though the novel was completed over the last three years, the seed of it was planted long ago. In college at Montana State, after my wife called me to become a much more devoted reader than I had been, I began to go back to Montana’s most cherished writers and two of them started me on a long and beloved journey: A.B. Guthrie and Ivan Doig. Specifically Guthrie’s The Way West and Doig’s This House of Sky. So Montana itself is the genesis of American Copper.

With American Copper I wanted to write a love song to Montana—to Montana’s people, all of Montana’s people, and to Montana’s wilderness. Though the novel was completed over the last three years, the seed of it was planted long ago. In college at Montana State, after my wife called me to become a much more devoted reader than I had been, I began to go back to Montana’s most cherished writers and two of them started me on a long and beloved journey: A.B. Guthrie and Ivan Doig. Specifically Guthrie’s The Way West and Doig’s This House of Sky. So Montana itself is the genesis of American Copper.

DA: American Copper is a Butte novel through and through. Once billed as “the largest city west of the Mississippi between Chicago and San Francisco” (but now ranked as Montana’s fifth-largest city), Butte has a–pardon the pun–rich history. What in particular attracted you to the Mining City?

Signing at the recent Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association Tradeshow

SR: I was drawn to the industrial machine of America in full swing, in the middle of such sheer mountains and crystalline river valleys, on the slopes of the Continental Divide. There is often such ungodly dominance and privilege in those with privilege, and Butte had more money than we can imagine. At one point, Butte supplied the electricity, the copper conduit, for 60 per cent of the world; over the course of the mining in Butte, the Rockefellers and Clarks of the world made a killing—about 300 billion dollars came out of that hill; the city was like a small New York in its heyday, cosmopolitan, with streetcars, liquor flowing as if from in an inexhaustible fountain, gambling, wars among the copper barons, a very fine theatre, a huge amusement park, streets of whorehouses, and even prostitution underground. Butte was an underground city where those who liked their morality hidden could debauch themselves at will. What’s not to like?

DA: There’s an interesting use of the term “American Copper.” It conjures up the image of men wrestling minerals out of the rock-hard earth…but it also refers to the delicate beauty of Lycaena phlaeas americana, the American Copper butterfly, which a young Evelynne and her father observe “flickering like minuscule fires” along the banks of a river. At what point did the butterflies come to you–and was the metaphor one of those proverbial “light bulb moments” we writers cherish?

SR: When I found the butterfly, I was so thankful. I write mostly at night when darkness falls and I feel a sense of grace living as a man in a house where my wife and daughters sleep. All is quiet in the house at night. Listening to what emerges from the silence is central to the writing. On one of those nights I was looking up American Copper and finding, as you might imagine, copper companies, copper architecture, pipes, roofing products, and various copper bric-a-brac. But one of the most prominent listings, perhaps even the first listing, was for a butterfly that I immediately recognized from days spent with my father in the Beartooth Range in southern Montana. I recalled those very butterflies, gossamer and shimmering in bright burnt orange with black spots, hundreds of them along the paths we walked. As I read on, I discovered that in Montana, these butterflies common to my own childhood, are called American Copper. The moment stunned me. The book was nearly finished. This final thread, like a red thread in a tapestry, informed the entire arc of the novel.

DA: The titles of both your books of fiction begin with “American.” Is this by design?

SR: At present I’m thinking of an American trilogy. So I’m considering a third book in this line and beginning to take down notes and thoughts. I believe it would be set closer to the present, with perhaps a few descendants of Evelynne and Black Kettle along with a larger American mix of race, gender, and class.

Also, have you ever heard the “American Trilogy” by Elvis? Who doesn’t love Elvis, sweat pouring down, his voice belting like a locomotive?

Also, have you ever heard the “American Trilogy” by Elvis? Who doesn’t love Elvis, sweat pouring down, his voice belting like a locomotive?

DA: Can you tell us a little bit about your relationship with independent booksellers? How did they impact the sales and reception of your books?

SR: Independent booksellers are the heart and soul of everything great in American book life! They gave such support and open-heartedness to me with the story collection American Masculine,I’m still moved thinking of specific booksellers that have made a tremendous difference to me personally. In order to thank them I wrote brief love essays (run at Tin House online, and NW Book Lovers) to each of the following three bookstores: Elk River Books in Livingston, Montana; Auntie’s Bookstore in Spokane, Washington; and Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, Washington. I think of Andrea Peacock and Marc Beaudin at Elk River in my former hometown Livingston, Montana. I’ve never seen a place with such a purposeful and beautiful tradition of hand-selected titles. I think of Jess Lucht at Auntie’s in my current hometown Spokane, Washington. Spacious and homey, Auntie’s has large wood stacks and hardwood aisles, and very thoughtful booksellers who can handsell with the best of them. And I think of Laurie Paus of Elliott Bay in Seattle. What a person! What a store! A landmark of Seattle’s art scene. Laurie set up my reading there, and we had a beer and talked about Robert Frost’s poem “Directive,” and became friends for life. If I name the gifts of the amazing independent booksellers I know, what comes to mind is friendship, dedication, and kindness.