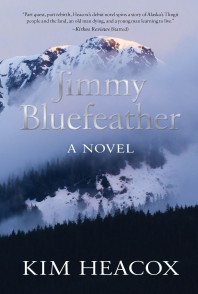

Jimmy Bluefeather, the new novel from award-winning writer, photographer, and conservationist Kim Heacox, is the first work of original adult fiction released by Alaska Northwest Books in fifty-six years of publishing. The collaborators recently got together to discuss their groundbreaking effort.

AN: Alaska roots this novel and plays a large part in the overall story line. How does the perception of Alaska as a kind of mysterious and remote place play a part in Jimmy Bluefeather? Why can’t the story have happened anywhere else?

KH: This story is an after-image of the ice age. It’s set in a wild coastal world of storms, bears, mountains, whales, temperate rain forests, and tidewater glaciers. It’s set in Alaska, the America-that-used to-be, where rivers of ice run from the mountains down to the sea and calve massive pieces of themselves into inlets and fjords and create icebergs that provide nursery platforms for seals to give birth to their pups. It’s a land of eagles and ravens, of rebirth and resilience; a coming-back-to-life place in the wake of a massive glacial retreat. As such, that resilience infuses everybody who lives there, even an old man like Keb Wisting. The land itself, cut and carved by glaciers, is still youthful and wild, patterned by the tracks of wolves and bears. It inspires him to be young again, to finish carving his last canoe and take off, undaunted by the wind or rain. Such a thing could hardly happen in a cornfield or a city, in a shopping mall or a subdivision.

AN: What was your biggest challenge in writing about Keb? Is there another character you enjoyed bringing to life?

KH: First, to endear the readers to him; make him likeable, believable. Second, to cross the age and culture barriers with accuracy and respect. I’m not Norwegian, Tlingit, or ninety-five years old. I’ve spent time with Norwegians (been to Norway several times) and with Tlingit elders (living as I do in Southeast Alaska) and always found them to be engaging, quick-witted (often with great senses of humor), soft-spoken, and wise; rooted in the past, yes, but also much more attuned to modern life than you’d think . . . knowledgeable about things like politics and basketball. I also enjoyed developing Anne as a character, since the novel moves from Keb’s point of view to hers. I enjoyed writing about her budding romance with Stuart, something I didn’t have in earlier drafts.

AN: What was the genesis of publishing Jimmy Bluefeather?

KH: I began writing it in September 2002 and finished the first draft in three years, and put it away (thinking: Yikes, what have I just done?). Months later I reread it with new eyes, cut it by 20 percent, filled out a few characters and scenes, and tried to sell it. Rejections rolled in, many on beautiful letterhead (all rejections today come by e-mail and make less interesting keepsakes, unless they’re brilliantly written—few are). I hired a manuscript doctor, revised it again, tried selling it, hired another manuscript doctor, added a new epilogue, let it sit for another year, then found a literary agent—Elizabeth Kaplan—who read it in three days and loved it. More rejections. I let another year or two go by, and revised it again. Random House and Henry Holt came close to taking it. Then one day, almost as an afterthought, I sent the manuscript to Doug Pfeiffer at Alaska Northwest Books (“Hey, Doug, how are you? Look what I’ve been working on.”). I’ve known Doug for twenty-five years, but wasn’t sure he was interested in publishing fiction. He loved it, made an offer, and here we are. My advice to writers: write for the joy of it, not to be rich or famous (whatever that is). Tell a good story. And never give up.

KH: I began writing it in September 2002 and finished the first draft in three years, and put it away (thinking: Yikes, what have I just done?). Months later I reread it with new eyes, cut it by 20 percent, filled out a few characters and scenes, and tried to sell it. Rejections rolled in, many on beautiful letterhead (all rejections today come by e-mail and make less interesting keepsakes, unless they’re brilliantly written—few are). I hired a manuscript doctor, revised it again, tried selling it, hired another manuscript doctor, added a new epilogue, let it sit for another year, then found a literary agent—Elizabeth Kaplan—who read it in three days and loved it. More rejections. I let another year or two go by, and revised it again. Random House and Henry Holt came close to taking it. Then one day, almost as an afterthought, I sent the manuscript to Doug Pfeiffer at Alaska Northwest Books (“Hey, Doug, how are you? Look what I’ve been working on.”). I’ve known Doug for twenty-five years, but wasn’t sure he was interested in publishing fiction. He loved it, made an offer, and here we are. My advice to writers: write for the joy of it, not to be rich or famous (whatever that is). Tell a good story. And never give up.

AN: Could you discuss the transformation of the relationship between Keb and James as the story evolves?

photo by Kim Heacox

KH: Through a profound experience (the canoe journey), they come to understand and trust each other and develop great respect for each other. It’s not an easy transformation, just as travel by canoe is not always easy. It’s hard, and it’s the “hard” that makes it great. Early on, Keb dislikes much of what he sees in James. James in turn regards his grandfather as a relic waiting to die. They love each other, of course, but they don’t easily relate to each other. The canoe—and wild Alaska—changes all that. The story opens in May and closes in September, and a lot happens in that time. Not until a later draft did I land on the epilogue, with the rebuilding of the Keb Shed, and James (Jimmy) using his hands so artfully, beginning to show the mannerisms and speech of his grandfather.

AN: Is there a symbolism between James and the canoe?

KH: Yes, the canoe is James’s new legs. It’s his new freedom and identity after ruining his leg (and basketball career) in a logging accident. The idea of the canoe floating above all his grief—the ocean of his loss—appeals to me. I’ve known young athletes who’ve suddenly faced the end of their careers. It devastates them. They struggle for years, if not entire lifetimes, to find themselves again. The canoe saves James; it gives him new purpose. It allows him to work with his hands, to paddle into his terror and his potential, to become an artist in a new and rewarding way, one that will enrich the rest of his life.

AN: You discuss the struggle between tribal and environmental issues. How does that affect the story? Is this happening in current news?

KH: Keb’s two daughters, Ruby and Gracie, see things differently. They love each other, but don’t always respect each other. This breaks Keb’s heart. His three sons are dead. Ruby and Gracie are his only remaining children, and he wants them to get along. He wants peace in his family. But large modern forces get in the way: politics and power, primarily, built on the idolatry of money, which in turn is built on an economic model that’s addicted to growth and never full, never satisfied. Ruby is pro-Native corporation while Gracie is not. This goes back to the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that created a dozen regional Native corporations and 200-plus village Native corporations across the state. While Ruby and Gracie both want to return to their ancient homeland, Crystal Bay, Ruby wants to capitalize on its mining and tourism potential, while Gracie wants to take kids and elders there to pick berries and maybe one day hunt and fish (ceremonially) as in the ways of old. Then along comes Keb who goes back in his own way, by canoe, something nobody’s done in recent memory. Many Tlingits today talk about going back to their ancient homeland, but nobody does it in the ancient way, by canoe. In fact, the art of canoe carving is largely gone today. So to think of an old man finishing his last canoe and taking off for the glaciers that shaped the geography that shaped him—I found this a powerful story line to explore.

AN: What’s up with Steve?

KH: Ah, yes, Steve the Lizard Dog. People love dogs. I think a good story can be improved by a quirky, endearing dog. Look at Snoopy in the cartoon strip Peanuts. He’s comical but also wise. Look at John Muir and Stickeen and their amazing adventure together on the Brady Glacier in 1880. I brought along Steve to help develop all the other characters in the town of Jinkaat, and in the canoe: Old Keb, James, Kid Hugh, and Little Mac. Each has his/her own relationship with Steve, and that’s fun. Also, early on we discover that Steve irritates some people, but not Keb. Keb likes him, and sees his goodness. This helps to develop Keb and Steve as characters that benefit from each other’s company.

AN: How does Jimmy Bluefeather shed light on Alaska Native tradition and perception of family and place? How are they caught between times and places and how are they meshing them together?

KH: For thousands of years the Native peoples of the great canoe cultures of the northwest coast of North America lived extraordinary lives, traveling far, living large. They read the tides and stars and storms; they knew every plant, every track in the sand, every salmon stream and red cedar grove. In the novel I describe Keb and his cohort as being “liquid people” who wore the rain like a second skin. In just a couple hundred years (1780s-1980s) all that changed. The canoe culture is largely gone now, and with it some of the wisdom it engendered. Yet Keb still has it in his bones and blood, from his childhood. He was born just in time to live the last vestiges of it. I created Keb to bring the canoe culture back, to represent a piece of that past that lives on, despite all the distractions and trappings of modern civilization and runaway consumerism.

AN: Of all the wisdom Keb shares, which predominant life lesson(s) would you like readers to take away?

KH: Don’t die before you’re dead. Most of your limitations are in your head. Dig deep and live young, even when you’re old. Find what you’re most passionate about (in Keb’s case, carving a canoe and traveling by canoe), and do it. Honor the past and where you came from without being blinded by ideology and too much money; stay open to new ideas and other ways of seeing and being, to what’s really true. Honor and caretake the elderly but surround yourself with young people. Be thankful. Live in gratitude. It’s seldom too late to be young again, to find the vibrant you that you might have stopped being long ago. Oh yes, and don’t let anybody take away your language, force you to wear tight shoes, or put too much sugar in your nagoonberry pie.

Kim Heacox is the award-winning author of several books including the acclaimed John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire (which received starred reviews from Kirkus, Booklist, and Publisher’s Weekly) and Rhythm of the Wild. His feature articles have appeared in Audubon, Travel & Leisure, Wilderness, Islands, Orion, and National Geographic Traveler. Kim was also commentator, along with Gretel Erlich and other environmental VIPs, on Ken Burns’ 12-hour PBS film The National Parks, documenting the history of the national parks and the U.S. conservation movement. A contract writer with the National Geographic Society since 1985, Kim has twice won the Lowell Thomas Award for excellence in travel writing and was a finalist for the Pen Center USA Western award for his memoir, The Only Kayak.

The cover of Jimmy Bluefeather features an image by Heacox, whose photographs are sold around the world by Getty Images. When not playing the guitar, doing simple carpentry, or writing, he’s sea kayaking in Gustavus, Alaska, gateway to Glacier Bay NP with his wife, Melanie. Learn more at www.KimHeacox.com. Watch for author events in the Pacific Northwest this fall.

I can identify with Kep and my favourite saying was “don’t die before your dead”

Thank you for a truly remarkable book , wish Old Kep was a real person , you made him real

Kim your book is inspirational