If I could give every teenager in the world one thing, it would be J-Hall.

If I could give every teenager in the world one thing, it would be J-Hall.

When I was in high school, J-Hall was my haven. The nerds ruled J-Hall. It housed the band, choir, and theater departments, and at the end of the hall, far from the clamor of the crowded cafeteria, sat a magical secret—a little, cluttered storage room for old theater costume fabric—the sewing room.

Those who knew could slip away to the sewing room during lunch. There, on a battered old couch, you were safe. You were safe to be that kid who carried around a briefcase instead of a backpack. You were safe to be that girl who drew ridiculous comic books about Frenchmen. You were safe to be that super-senior who struggled and got called a failure, but could play the guitar like it was a part of him, so sweet and soft it made you want to cry. You were safe—and more than that, you were celebrated.

I don’t like the term tolerance. It comes up often in education; we teach tolerance, we promote tolerance, and we even enforce tolerance through disciplinary action . . . but I’m not a fan. Don’t get me wrong, I much prefer it to intolerance—respect for diversity is essential in a school—but tolerance is not respect. Tolerance connotes a grudging, unpleasant acceptance. You tolerate a foul smell and you tolerate the taste of kale. I don’t teach my students to reluctantly tolerate diversity, I teach them to celebrate it.

To be honest, celebrating diversity is an easy lesson. For the most part, kids already tend to assume that everyone else is infinitely more awesome than they are, and they embrace the chance to be inclusive and supportive. The real trick is helping them to celebrate themselves, too. That’s the harder lesson, and not every student has J-Hall to teach it to them.

To be honest, celebrating diversity is an easy lesson. For the most part, kids already tend to assume that everyone else is infinitely more awesome than they are, and they embrace the chance to be inclusive and supportive. The real trick is helping them to celebrate themselves, too. That’s the harder lesson, and not every student has J-Hall to teach it to them.

I try to be J-Hall for my students. I hang the Safe Schools posters on the wall and open my door during lunch. I tell my students to be weird, to celebrate strange, and to learn to love odd. I spout, with great vigor, phrases like “Every exceptional human being in all of history is—by definition—an exception to the norm!” and “You’ll never become extraordinary if you’re too busy being ordinary!” I promote being a nerd—because nerds are the ones who have learned to be passionate about the things they love without shame or regret. I wear bow ties to class, I get overexcited about books, and I host the school’s burgeoning My Little Pony club.

In the end, however, no matter what else I am, I am not a cluttered sewing room at the end of the hall—and this might be my greatest disappointment as a teacher. I can’t give J-Hall to my students, but I can give them the next best thing. I can give them a book.

I can show them the way to the House on Mango Street or the path to the Shire. I can introduce them to Atticus Finch or Theseus, and let them invite Katniss Everdeen or Harry Potter to class. That’s why I’m a book-pusher. The truth is, for all my grading and lesson-planning, I know with certainty that the most meaningful thing I did all year for at least one student was to push a copy of If You Could Be Mine across her desk. She read it twice in one night. Sara Farizan didn’t judge her. She was safe there.

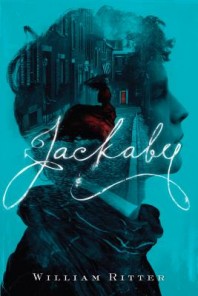

Tegan Tigani, editor of nwbooklovers.org and huge “Jackaby” fan, with Will Ritter at Queen Anne Book Co.

My greatest hope for my own novel is that someday it will be that haven for a reader—if only for a few hundred pages. In hopeful anticipation, I loaded it with optimistic themes about individuality and self-discovery. “I have ceased concerning myself with how things look to others,” Jackaby tells his young narrator. “Others are generally wrong.”

I don’t especially mind if I never win any fancy awards or sell a million copies. The greatest, most profound honor any book can receive is to become—for one reader at a time—that room at the end of J-Hall. If I could, that’s what I would give to every teenager in the world. I would push it right across their desks and allow them a little time to visit it at the start of every class.

William Ritter began writing Jackaby in the middle of the night when his son was still an infant. After getting up to care for him, Will would lie awake, his mind creating rich worlds and fantasies—such as the one in New Fiddleham. Will lives and teaches in Springfield, Oregon. Jackaby, on sale September 16, 2014 from Algonquin Young Readers, is his first novel.