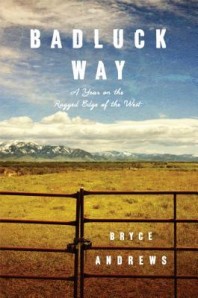

Bryce Andrews made a strong impression on his bookseller audience at the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association tradeshow in October. His memoir, Badluck Way: A Year on the Ragged Edge of the West, is a thoughtful adventure into the windswept plains of Montana, across which he maps the physical and spiritual endurance necessary to keep himself and the cattle he’s been entrusted with alive while trying to find a distance at which to embrace the wild residents of the area.

Bryce Andrews made a strong impression on his bookseller audience at the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association tradeshow in October. His memoir, Badluck Way: A Year on the Ragged Edge of the West, is a thoughtful adventure into the windswept plains of Montana, across which he maps the physical and spiritual endurance necessary to keep himself and the cattle he’s been entrusted with alive while trying to find a distance at which to embrace the wild residents of the area.![]()

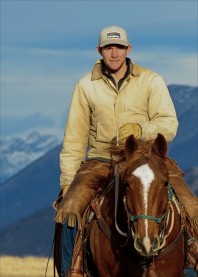

![]() Andrews and Kristianna Huntsberger met to talk at Café Allegro in Seattle’s University District, a spot where he frequently came to work while editing Badluck Way.

Andrews and Kristianna Huntsberger met to talk at Café Allegro in Seattle’s University District, a spot where he frequently came to work while editing Badluck Way.

KH: You talk about dark places being magnetic and being drawn to the unknown. Throughout your book there are a couple strong elements of risk, like wolves, weather, and the unfamiliarity of everything. Thinking back to your first move to Montana, how did you experience these risks?

BA: We went to Montana every summer when I was growing up because my father is a rabid fly fisherman. I remember as soon as we crossed the Cascades and got out into Eastern Washington everything would just flatten out. I felt like my whole heart would flatten out too. You feel this spreading of yourself across a wider horizon. I loved the space and that was part of what drew me to Montana. I also liked the rawness of it.

I have this image that has been with me as long as I can remember of a bunch of people sitting around the campfire and somebody leaving the circle of the firelight and going out into the darkness and doing something there that the other people can’t see and don’t necessarily understand, and then returning with the story or news from the darkness. I don’t know whether I thought it then, but that is how my mind was working when I made the decision to go to Montana. What is weird about it is I still live there. I didn’t do what I set out to do, which was to go into this wild place and do some specific thing with a specific time limit and come back with a story. I wrote a story, yes, but I still live there. I never really came back. Maybe you can’t come back if you stay long enough in the wild places. I really think that people change to fit the places that they live. I think the landscape shapes us in a way that we never fully understand or accept. It is hard to accept that I might be a certain way from growing up in the Pacific Northwest with only little glimpses of the sun, but sometimes I feel it when I am talking to people that I work with now. We do the same rough work of ranching in Montana, and yet I see things very differently. I think part of that has to do with the culture I grew up in, but also part of it has to do with the landscape.

I have this image that has been with me as long as I can remember of a bunch of people sitting around the campfire and somebody leaving the circle of the firelight and going out into the darkness and doing something there that the other people can’t see and don’t necessarily understand, and then returning with the story or news from the darkness. I don’t know whether I thought it then, but that is how my mind was working when I made the decision to go to Montana. What is weird about it is I still live there. I didn’t do what I set out to do, which was to go into this wild place and do some specific thing with a specific time limit and come back with a story. I wrote a story, yes, but I still live there. I never really came back. Maybe you can’t come back if you stay long enough in the wild places. I really think that people change to fit the places that they live. I think the landscape shapes us in a way that we never fully understand or accept. It is hard to accept that I might be a certain way from growing up in the Pacific Northwest with only little glimpses of the sun, but sometimes I feel it when I am talking to people that I work with now. We do the same rough work of ranching in Montana, and yet I see things very differently. I think part of that has to do with the culture I grew up in, but also part of it has to do with the landscape.

KH: What are some of the differences that you see in your perspective from that of your peers in Montana?

BA: I have had to start from scratch in a way that someone who grew up in that context, with ranching as part of their family history, doesn’t. When you grow up with animals around you, you become very familiar, early on, with death and with loss and birth and growth and increase and all those things. Those things were abstract to me when I went out there.

I guess I inherited a different set of assumptions about how a human should be in relation to landscape. You have to remember, that if I grew up anywhere, it was in an art gallery because my dad ran the Henry Art Gallery [in Seattle] for a long time. The defining factor of an art gallery is that you cannot touch any of these beautiful, amazing things. That is the cardinal rule of being a kid in an art gallery: you can’t mess with stuff. The defining quality of ranching is that you have to mess with stuff. Everything has to be touched, everything has to be moved. Things have to be broken and fixed, depending on what the day demands of you.

I guess I inherited a different set of assumptions about how a human should be in relation to landscape. You have to remember, that if I grew up anywhere, it was in an art gallery because my dad ran the Henry Art Gallery [in Seattle] for a long time. The defining factor of an art gallery is that you cannot touch any of these beautiful, amazing things. That is the cardinal rule of being a kid in an art gallery: you can’t mess with stuff. The defining quality of ranching is that you have to mess with stuff. Everything has to be touched, everything has to be moved. Things have to be broken and fixed, depending on what the day demands of you.

KH: There were interesting juxtapositions in the book of human presence and the natural world. You show us bones of animals and bones of industry side-by-side on the ranch. How did your feelings about the human relationship to nature change out there?

BA: My relationship with the natural world became very immediate and participatory on the ranch. You are in a weird position as a ranch hand. On one hand, you are working at odds with the natural world because you are trying to take your crop, whether it be cattle or whatever you are growing, and you are trying to shoehorn it into a little niche in a functioning, ecological system. You do feel like you’re pushing against the wildness. You’re trying to push your way into a spot where you can actually make a living. But, if you’re thinking about it, you realize you can’t survive without that natural system functioning. You must engage with nature in a way that is supportive and destructive at the same time. That sounds like a contradiction and it probably is, but that is just the way that it always seemed to me. You don’t know whether you’re building or destroying half the time.

If you come from where I did, you are seeing yourself in the landscape as you are working, because in the back of mind I was always aware that I was doing something very different from what most of the people I grew up with were doing. I guess when I started I lived a little on the assumption that there was something heroic about it or something mythic about what I was doing. I think it is interesting to go through the book and look at how that sense of heroism and the mythic west goes away as the book goes on.

KH: It is great to think about the book as a progression from the mythic introduction, toward becoming part of an integrated landscape.

BA: Yeah, I remember the Henry Art Gallery had this show, “The Myth of the West.” It was this defining moment for me as a kid. It was this spectrum of art about the American West over time. It went all the way from the earliest sketches and the landscape painters, like Bierstadt, all the way up through Andy Warhol’s “Double Elvis.” It is something I still think about all the time. My mom is a photographer and I just gave her two books for Christmas. One is by Evelyn Cameron, who was one of the first photographers in Montana and she was part of this big ranching family and she documented everything. The second book was one of these modern attempts to see art in the west. And this distinction between documentation of the reality and documentation of the myth is really interesting to me.

The myth of the west represents interesting things and some really interesting possibilities. It is something a lot of us believe in; this idea of an empty landscape that a person can work upon and the idea of a person reflected in the landscape. That is a tremendous tool for motivating people to do the right thing. At the same time, it is also dangerous because we end up with a placeless west. That is what the Double Elvis always means to me. We are watching the myth and the land diverge. For me, the idea that those two things could come back together is important. If I could contribute something, I would want it to be to help attach those things again. When they are attached, that is when we can do right by the land, which, at the end of the day, sustains us all.

KH: What is the role and future of conservation ranching?

BA: That is a complicated one to answer. I think we need to build landscapes that are working mosaics. For instance, I am in the process of leasing this ranch just outside of Missoula with a friend of mine and we are going to raise grass-fed cattle. The neighboring place is a wildlife preserve. We need both of those things in the landscape. We need to make space for our wild creatures, especially our difficult ones, like the wolves and the bears. At the same time, we have to keep in mind that if our stewardship of the landscape depends year-to-year on the generosity of some millionaire or billionaire who buys a place and takes it out of production and pours vast resources into it, then the whole thing rests on the continuation of that wealth. I think it is a lot stronger to build a landscape where people are able to make a sustainable living from the land. If you have people producing crops and cattle in a way that works with the natural world, as much as is humanly possible, I think that is more secure in the long-run.

KH: Your different perspective may have helped you view the situation on the ranch in its complexity. This brings me back to the idea of risk we started with and the risk you took in writing about the subject. How did you negotiate the risk of writing this, even knowing the strong social and environmental energies invested in the topic?

BA: When I was sending this book around to people who were in it, James’s wife, from the book, said to me, “Bryce, this is a book that Environmentalists are going to wave in our faces for the rest of our lives.” She was unhappy about that. Within forty-eight hours of that conversation, I got an email from a distinguished author from Seattle and he said, “This is a book that ranchers are going to wave in our faces.” Verbatim. They both said the same thing, with the sides transposed. And I though, ok, that should tell me something. There is no making everybody happy here because this is a messy thing and it is a bloody and a complicated thing.

The first article I published ever was about shooting the wolf. It was in High Country News and it came out one week before I started in the Environmental Studies Master’s program at the University of Montana. I had people calling my landlord wanting to get me thrown out and people tried to fight me, drunkenly, in the street. It was interesting to understand, very personally, how much people care about this. The wolf thing in particular is really hard for people. Sometimes I kind of miss what it would have felt like if I had never been in the mud of it because it must be really clean from a distance. It must be clean and black and white and there must be concrete right and wrong to the thing. What I have learned from this whole experience is that the closer you get to an actual wolf or an actual cow; the closer you get to the actual situation, the harder it gets to view it that way.

The first article I published ever was about shooting the wolf. It was in High Country News and it came out one week before I started in the Environmental Studies Master’s program at the University of Montana. I had people calling my landlord wanting to get me thrown out and people tried to fight me, drunkenly, in the street. It was interesting to understand, very personally, how much people care about this. The wolf thing in particular is really hard for people. Sometimes I kind of miss what it would have felt like if I had never been in the mud of it because it must be really clean from a distance. It must be clean and black and white and there must be concrete right and wrong to the thing. What I have learned from this whole experience is that the closer you get to an actual wolf or an actual cow; the closer you get to the actual situation, the harder it gets to view it that way.

The book is not about taking a position. I don’t think it is my place to tell people, “Here is how we should behave in respect to the wolf.” I just wanted to write the truth of what happened out there and I felt very strongly that, risks aside, controversy aside, I had been very fortunate to live through a story that most people won’t get to see in their life time, something that is going to be more rare in a world and a landscape that gets more crowded every day. Every generation has left the American West more crowded and less intact than the last one. There are definitely risks to writing about this stuff, but at the same time, the benefits of it and the urgency of it, to me, outweigh the risk.

KH: What are you doing now in Montana?

BA: I am working on a second book. It is about the upper Clark Fork where I managed a ranch for about five years. It is a beautiful place, wild on the edges, but also the nation’s largest Superfund site, from the Butte and Anaconda copper mining. It is a book about the social and ecological consequences of what happened there. Forty miles of the river are contaminated with arsenic, lead, copper and cadmium. What I was doing was running a ranch for a conservation group that included four miles of that river and a bunch of other land, trying to rehabilitate that land using cattle as a tool and also trying to build support in a suspicious and long-beleaguered community for this clean-up that was coming down the river. Also, like I told you, I just leased a ranch with a friend of mine. I guess it goes back to what I was saying, if you are going to talk about this stuff, you have to keep doing it. If you stop doing the work, number one, you get miserable because you are inside all the time, and number two, you don’t get to talk about it anymore.

January 17 at Powell’s— Reading and signing at 7:30