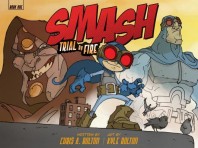

Chris and Kyle (right) Bolton

The Nightcapper event at Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association’s fall tradeshow in Portland in October hosted a variety of exciting new authors. There I bumped into Chris and Kyle Bolton, the sibling team behind Smash: Trial by Fire, the first book in the superhero graphic novel series for young readers, aged 7 to 12. The book follows ten-year-old Andrew as he adjusts to the greatness thrust upon him when a sinister plot gone haywire gives him amazing superhero powers. Chris’ energetic storytelling and Kyle’s bright illustrations capture readers in the thrill and confusion of Andrew’s new powers and leave us all wondering what will happen to the hero as he tries to grow into them.

Kyle and I sat down at a café in downtown Seattle to talk about the birth and development of Smash. —Kristianne Huntsberger

KH: What is your history with comics and who are your influences?

Kyle: At a young age I was into an artist named Michael Golden. He was able to take the comic book world and translate it into a visual language that I could finally understand. But, what really turned me around was when my Mom got me a Norman Rockwell book when I was about 12. I loved it. It was like 50 pounds. I couldn’t believe that someone could paint so realistically and yet it was so loose and stylized. It was only later that I learned that Rockwell was copying J. C. Leyendecker, who was a much better illustrator. I put Rockwell away and became a Leyendecker fan.

Kyle: At a young age I was into an artist named Michael Golden. He was able to take the comic book world and translate it into a visual language that I could finally understand. But, what really turned me around was when my Mom got me a Norman Rockwell book when I was about 12. I loved it. It was like 50 pounds. I couldn’t believe that someone could paint so realistically and yet it was so loose and stylized. It was only later that I learned that Rockwell was copying J. C. Leyendecker, who was a much better illustrator. I put Rockwell away and became a Leyendecker fan.

Also, there was illustrator named Bernie Wrightson who did this fantastic edition of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein. He did it all in pen with crosshatching and all this incredible detail and you just get lost in the picture. My brother has a copy he bought at Powell’s Books and he won’t let me borrow it because he had one when we were kids and we looked through it so much that the glue wore and the pages would just come out and I would try to shove them back in and he had this book with all these pages sticking out.

I didn’t originally start reading comic books. I was a kid and just kind of into the pictures. It was my brother, Chris, who was into the stories and, when I would ask, he would help delegate which were good stories. We didn’t go out of our way to make a comic book. It is just what kids do. You are a kid and you like to draw pictures and your brother will write in the words. The problem is we could never finish anything without fighting. Anything. A comic book, a game with toys, anything. So, yeah, it took a lot of years of maturity and took some time to put aside all the adolescence. I mean, we still fight, but it is more of a creative difference.

KH: The two brothers in the story, Andrew and his older brother, Tommy, have some brotherly tension. It made me wonder what it was like for you and your brother to work together and whether any of this was autobiographical.

KH: The two brothers in the story, Andrew and his older brother, Tommy, have some brotherly tension. It made me wonder what it was like for you and your brother to work together and whether any of this was autobiographical.

Kyle: I have three older brothers. I’m the youngest. Being the youngest, you see everyone as having something that you can’t get—I’m not old enough or not tall enough. So, being envious of your older brother is in the book. The fighting is in there too. But the tender moments are also there. I think if people with siblings look at this, they’ll see the brothers are fighting, but they still get along. And later on in the story it is important that they get along. In the next book, they realize that they depend on each other. The fact that they are brothers is really pivotal to Chris and I. It is one of those points that we can always say, “Ok, I know exactly what they are going through at this point and I know exactly how to do the expression and write the story,” because we lived it.

KH: What inspired you two to make a superhero of your own?

Kyle: Chis came up here from Portland for a visit maybe 10 or 12 years ago and we went to the comic book store like we used to. We looked around on the shelves and we didn’t find anything we wanted and it was depressing. We walked out, the two of us, shaking our heads and thought, what the hell happened to our favorite industry. We were dumfounded.

We saw the progression of the movies. As soon as the “Batman Begins” movie started, everyone wanted everything dark. Let’s do Superman dark, let’s do it all dark. Let’s make his uniform even dark toned, instead of light toned. The dark ages of comics. Let’s make characters more realistic so that when Hollywood producers pick up comics they can say, hey, that kind of looks like Robert Downey Jr. I can imagine him in this role. The characters lose their comic book appeal and look like models. That’s where the proportions come in and how they objectify women’s proportions and create this stigma that women can be heroines, but they have to be sexy. It creates this huge divide because there are girls who read comic books but can’t see comics that are respectful of the human form in a way that anyone can just pick them up and connect with the characters.

KH: Was Smash created for certain individuals to identify with?

Kyle: The way I drew him, I didn’t want any muscles. I wanted him to be exaggerated, but you knew he was a kid. What I did actually was blow everyone’s proportions way out, except for average citizens. I wanted to design him so that any kid could look at him and say, “That could be me under that mask.”

KH: There was the moment when Smash’s size was a benefit and he could slip out of things in a way that large characters couldn’t. It immediately made me think this was the kind of story a kid wants to relate to because there are the bullies and the giants that can do all these powerful things, but he realizes ways his small stature makes him important.

Kyle: Chris was very smart in creating a point in the story where he has superpowers and yes, he could beat up these bullies, but if he does, he blows his secret identity and so he lets the bullies beat him up, but he smiles because he can’t feel anything. It was one of those moments when Chris looked at the larger point we are trying to get across—that with great power comes great responsibility—which applies to every superhero. Even at age 10 we want him to be self-aware that if he blows his identity he can’t help people any more. And we wanted kids to connect with that.

KH: This was a question I had. You give a kid super powers and he instinctively does good with them. How do you think he knows to do this?

Kyle: I think he was just kind of following the lead of the superhero Defender and just trying to emulate him at first and really quickly he realizes he’s not Defender. I think with superpowers, it is instilled in our DNA, we are supposed to do good. It is the Superman thing. When you can fly, when you’re stronger than you are supposed to be, you help people. People are generally good and would love to do great things, but they find themselves limited. As soon as we have powers, we snap into the things we wish we could do. We all want to help, deep down inside.

KH: Smash learned by watching Defender. Do you think that you were also trained by superheroes in the comics you read as a kid? And, this is the question we ask artists and writers all the time, do you have a responsibility, as authors of a comic, to instruct or teach moral lessons?

Kyle: Anyone who is going to put something out in the public has to take on some sense of responsibility. We’re reaching an audience of kids. I think the mold has been set for what a superhero is and what you should do when you get super powers. With earlier comic books it just seemed so natural. They were pulling from Greek gods when they created their superheroes. Greek gods were not perfect, but in the stories they’re always doing amazing things. Authors pull from that. They have this character who is strong and catches the bank robbers and doesn’t kill them, but catches them and makes them go to jail and serve time for the crime they committed. That teaches right and wrong; justice must be served. Those things are the building blocks of creating superheroes.

We are taking on a little bit of responsibility for clean fun; making a good action comic that kids can get into and people our age, who have kids, won’t have to worry about whether the material is safe. We make the effort to send out a good message. Smash is trying to be a good guy, he is using his powers for good. Hey, maybe you should too.

KH: We were talking earlier about how your first Smash book has filled an important age-group gap.

Kyle: We were told that by the librarian at the school that we visited because she said there was this age range where kids have a hard time finding something parents feel is safe, but that the kids are also interested in. She said Smash filled that gap. Usually books were too graphic or too childish for these kids. They want choices. Smash is in that section with Bone and Amulet. We spoke also to a woman at Mockingbird Books and she said since Smash and other titles have come out, that section of kids’ graphic novels has grown, and she loves to bring kids around to that section.

Kyle: We were told that by the librarian at the school that we visited because she said there was this age range where kids have a hard time finding something parents feel is safe, but that the kids are also interested in. She said Smash filled that gap. Usually books were too graphic or too childish for these kids. They want choices. Smash is in that section with Bone and Amulet. We spoke also to a woman at Mockingbird Books and she said since Smash and other titles have come out, that section of kids’ graphic novels has grown, and she loves to bring kids around to that section.

KH: You and Chris have hosted comic workshops in school libraries to explain all the steps to make a comic. How do you start a comic, with the images or the text?

Kyle: Oh, the image never comes first. Chris has an outline, and the structure and then the script. And once the script is given to me, I read it and then we start the collaboration. Nothing is on paper yet. We say, “OK, in this scene he’s supposed to do this, but how about instead he does that?” The fights come from this stage. We like our character, we both connect with him, we are both living in this world that he lives in, but we see it differently. It is the same vision, but we argue over the details. For example, Chris didn’t really like the Seattle skyline; he wanted Portland. And I said, “But, Seattle is great.” So, basically, we put Portland and Seattle together. So it’s Seatown. It’s just little collaborations like that.

KH: So, Chris presents the script and you both maneuver the changes then you draw the panels?

Kyle: Once we come to consensus, yes. Even when I’m drawing the panels things are changing. I try to plot out the action scenes. When I’m in the moment it is kind of like I’m watching a movie while I’m drawing. It is structured and scripted out, but I kind of improvise, like I want this angle to change and then I stop everything and I show Chris. Then we have to go back-and-forth. It is the essence of the creative process.

KH: The book ends with an ellipsis. Where are we going? What is next for you guys and for Smash?

Kyle: In Book two, Smash will realize what the stakes are and that he really has to step up his game. With book two the world is much larger. There is a legacy of superheroes before him and there is a legacy of people he can learn from since he is going to be a superhero. I love that Chris did this. He has a group of retired superheroes that meet in a coffee shop and go over old times; what it used to be like and how fighting crime has changed. It reminds me of when I was a kid and I worked at a retirement home and I thought, that is exactly what I’m going to pull from. They’re all senior citizens. They’re going to be all original and colorful. Everybody’s going to be able to say, “That’s like my granddad” or “That’s my grandmother.”

The publisher is interested in the second book so hopefully we’ll hear some good news around the holidays. Chris has it mapped out and knows how many books there are going to be, though we haven’t agreed on an ending yet.