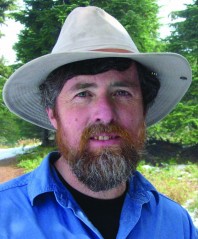

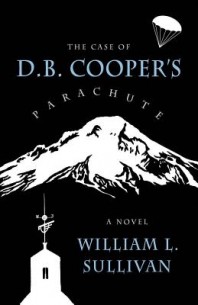

If you live in Oregon and enjoy hiking, you probably know William Sullivan as the author of many excellent guidebooks. He has written and published five hiking guides to cover different regions of the state, as well as additional books of special things to do and see in Oregon. His narrative nonfiction is also well-known; Listening for Coyote, the story of his hike across Oregon, is a modern classic and was named one of Oregon’s 100 Books by the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission, and Cabin Fever is a memoir of his family’s summers in the log cabin they built in Oregon’s Coast Range. But fewer people know that Sullivan is also a novelist. He has written four novels: A Deeper Wild, The Case of Einstein’s Violin, The Ship in the Hill, and now, The Case of D.B. Cooper’s Parachute, published October 1.

If you live in Oregon and enjoy hiking, you probably know William Sullivan as the author of many excellent guidebooks. He has written and published five hiking guides to cover different regions of the state, as well as additional books of special things to do and see in Oregon. His narrative nonfiction is also well-known; Listening for Coyote, the story of his hike across Oregon, is a modern classic and was named one of Oregon’s 100 Books by the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission, and Cabin Fever is a memoir of his family’s summers in the log cabin they built in Oregon’s Coast Range. But fewer people know that Sullivan is also a novelist. He has written four novels: A Deeper Wild, The Case of Einstein’s Violin, The Ship in the Hill, and now, The Case of D.B. Cooper’s Parachute, published October 1.

I’ve known Sullivan and his wife, Janelle Sorensen, for a long time through working in books. At both the Oregon bookstores where I’ve worked, he’s everyone’s favorite local author, because he drops in to say hello and autograph his books and has even been known to handsell them to customers. I never miss a chance to book him for an author event at Paulina Springs Books. Sullivan is humble but self-confident, a wonderful combination in an artist. He’s a dream to work with and gives entertaining slide shows that always delight our customers.

I’ve known Sullivan and his wife, Janelle Sorensen, for a long time through working in books. At both the Oregon bookstores where I’ve worked, he’s everyone’s favorite local author, because he drops in to say hello and autograph his books and has even been known to handsell them to customers. I never miss a chance to book him for an author event at Paulina Springs Books. Sullivan is humble but self-confident, a wonderful combination in an artist. He’s a dream to work with and gives entertaining slide shows that always delight our customers.

I met with Sullivan at Sisters Coffee Company before he gave his slideshow on Folk Heroes of the Northwest at our store. We talked about his novels, focusing on his newest, but also discussed the other two I’ve read, The Case of Einstein’s Violin and my personal favorite, The Ship in the Hill.

AM: Can you explain the historical D.B. Cooper, for readers who don’t already know?

WS: Oh-well, he walked into the Portland airport in November of 1971, bought a ticket to Seattle for eighteen dollars and fifty-three cents, and hijacked the plane. He asked for two hundred thousand dollars and four parachutes, jumped out somewhere over Mt. St. Helens, and has never been found. On one hand, he was the first airline terrorist, but most people see him as the swashbuckling bandit you want to get away.

WS: Oh-well, he walked into the Portland airport in November of 1971, bought a ticket to Seattle for eighteen dollars and fifty-three cents, and hijacked the plane. He asked for two hundred thousand dollars and four parachutes, jumped out somewhere over Mt. St. Helens, and has never been found. On one hand, he was the first airline terrorist, but most people see him as the swashbuckling bandit you want to get away.

AM: What made you want to write a mystery novel about this man?

WS: He’s one of the great folk heroes and mysteries of the Northwest, and no one had ever done it.

AM: Oh really? There are no other novels about him?

WS: Not really. There are screenplays and there was a schlock mass market thing that never really took off. There’s a slew of nonfiction about it, but they don’t say much—we don’t know much! That cries out for fiction. Also, I’m not embarrassed to be a regional author, and this guy characterizes so  much that’s quirky about Portlandia and all of the Northwest.

much that’s quirky about Portlandia and all of the Northwest.

AM: You’ve now written two mysteries, this one and The Case of Einstein’s Violin. Why did you make this book darker than The Case of Einstein’s Violin, which is a very good mystery but also just a romp across Europe?

WS: Actually, in a way, Cabin Fever is also a mystery, but it’s a true one, in which we attempt to solve a real murder, and it was an interesting book, but it was frustrating as a writer because the clues don’t come in the right order and you can’t wrap things up–there are a lot of loose ends.

In my first fiction mystery, I decided to buck tradition and not kill anybody, so people think it’s young adult. And it can be–there’s no death, no intimate sex. But for D.B. Cooper, it needs to be grittier. So it’s still not Steig Larson, but there’s more sex and violence. I think I have a body count of 16. It’s still not graphic, but in terms of sex, you do need a femme fatale. In this case, I made it be a librarian,  so she’s OK, she’s basically a good person.

so she’s OK, she’s basically a good person.

Because D.B. Cooper, the legend, has two faces, I needed two D.B. Coopers. He’s a folk hero and a terrorist. So I made it physically two. That makes the plot complicated, but it works. One is the folk hero we always dreamed of, and the other is a serial killer who’s blackmailing him and using his name. You’ve gotta have a good villain–it’s crucial in a mystery to have a good villain–and it can’t be D.B. Cooper.

AM: Is that because of the love for him here in the Northwest?

WS: Yeah, there are bars and festivals all over the Northwest named after him. He’s this folk hero, and if you tell people he’s a villain, they won’t be happy. Because of that, too, you want D.B. Cooper to get in trouble again and to have to escape again.

AM: You seem very comfortable with two genres: your hiking guidebooks and narrative nonfiction.  Yet you once told me you’re shy about your fiction. Is that still true?

Yet you once told me you’re shy about your fiction. Is that still true?

WS: Well, yeah. Before The Ship in the Hill I was shy about my fiction. I thought, “All I have to do is write a really, really good book and then sit back.” But there was no buzz. It sold a thousand copies, but there’s another thousand sitting in the warehouse at Partners/West.

So I learned with fiction, you have to tell people about it. So I did a music video; I did an author tour wearing D.B. Cooper-style sunglasses, I sent out lots and lots of advance readers–we sent out an advance review copy to every PNBA bookstore–and it won the PNBA BuzzBooks Award at the recent tradeshow. I went up to the show for one day, and I had the chance to tell a bunch of booksellers about The Ship in the Hill, and after my one-sentence elevator pitch, they all said, “That sounds great! Why haven’t I heard of it?” So I’m not shy about my fiction anymore.

AM: I know that you have traveled in Europe a lot, and that you’ve visited the places featured in your novels–Russia, Norway, Germany, Greece, and more. Did you travel to those places because you wanted to write about them, or did you go to them and then get inspired to write about them?

AM: I know that you have traveled in Europe a lot, and that you’ve visited the places featured in your novels–Russia, Norway, Germany, Greece, and more. Did you travel to those places because you wanted to write about them, or did you go to them and then get inspired to write about them?

WS: I’ll admit, in Einstein’s Violin we wanted to go to the Greek Isles, Germany, the Alps, and all those places, so I made a plot that required it. We traveled for six months, and I basically wrote the book on the trip and wrote it off as a business expense!

For Ship in the Hill I made five trips to Norway. And the Vikings conquered Russia. Russia is named after Rus, a Viking. We went to Murmansk . . . I knew I wanted a KGB connection for D.B. Cooper. You have to write on your passport what you’re going to Russia for, and I wrote I was researching Vikings and the Russian mafiya. Janelle said, “Can’t you just leave that off about the mafiya so we don’t have any trouble?” It turns out it’s very easy to research the Russian mafiya. Every guy you meet looks like he could be in it.

AM: You certainly spend a lot of time out hiking. Do you do any plotting for your novels in your head while you’re out on the trail?

AM: You certainly spend a lot of time out hiking. Do you do any plotting for your novels in your head while you’re out on the trail?

WS: Well, that’s true, actually. You know how it is; as soon as you finish one book, you start working on the next. I spend six months hiking and writing nonfiction, and six months in the winter writing fiction. I love that tradeoff. When you’re writing nonfiction, there’s all that creative energy looking for an outlet. So I’m making up subplots, thinking of scenes, memorable scenes that will stick with you. I know where the arc of the story is going before I start writing.

AM: Two of your novels, The Ship in the Hill and The Case of Einstein’s Violin, are written from women’s perspectives. Why did you choose to do that?

WS: As a novelist, I want a compassionate main character who is fighting against long odds. Historically, that would be a woman.

AM: I wonder if that’s why Tolkien used hobbits. They’re not typical heroes.

AM: I wonder if that’s why Tolkien used hobbits. They’re not typical heroes.

WS: Absolutely! They’re compassionate, they’re fighting long odds, and it turns out only a hobbit could overcome Sauron.

AM: Who are some of your favorite writers and/or writers who have influenced you the most?

WS: Knut Hamsun’s Hunger is probably still my favorite. It’s a noir novel set in Norway about a struggling writer.

Jo Nesbo–one of the characters in D.B. Cooper is inspired by a Jo Nesbo book, The Bat, not yet translated into English, except in Australia. It’s written in Norwegian. Well, I speak Norwegian, and I read this a few years ago when he was unknown, and it reminded me of Hunger. I was really impressed by the grittiness of his book. It was the mood that inspired me so much. Portland in winter reminds me a little bit of Oslo.

He had a character who partly inspired my Lieutenant Neil Ferguson. Nesbo’s detective is a wounded man walking, and Ferguson is too. One reader said it’s too much to have him struggling with alcoholism, have an autistic daughter, be a widower . . . But I thought if Nesbo could create a character with so much to deal with, I could too.

He had a character who partly inspired my Lieutenant Neil Ferguson. Nesbo’s detective is a wounded man walking, and Ferguson is too. One reader said it’s too much to have him struggling with alcoholism, have an autistic daughter, be a widower . . . But I thought if Nesbo could create a character with so much to deal with, I could too.

In this genre, you have to like your main character, and you have to want them to overcome.

AM: A lot of insights in your books come to the characters in dreams. Does this reflect how your mind works?

WS: For me, by far the most creative time is when I wake up in the morning. I go to bed with a problem, a character, a situation, and I wake up and those problems start to be resolved in that first waking up that is almost a dream state. There’s a part of you talking to you in the dream.

I’ve written parts of all these books at our log cabin. We have no television, no Internet, no visitors . . . So there’s nothing going on but your mind. I write on a typewriter, and the typewriter helps focus your thoughts because it comes right out in ink. The typewriter goes slower than your mind, which is a good thing.

AM: Can we look forward to another William Sullivan novel anytime soon?

WS: Actually, I’m working on short stories. I’m halfway through a book of short stories. It’ll be called The Oregon Variations, and it’s set in different places all around the state, and they’re all on the theme of loneliness, rotating points of view and primary characters.

AM: Well, every time my husband and I read one of your novels, we don’t want it to end, and when it’s over, we always say, “I don’t know what to read next. I just want to read another William Sullivan novel.”

WS: Thank you. That’s very kind of you to say.