Twelve years ago this summer, I sat at a campfire in a Central African forest, hearing the sad, horrific account of an Ebola virus outbreak in a nearby village. My two informants were Bantu men who had lost friends and loved ones in that outbreak. One of them, a shy fellow named Sophiano, with a body-builder’s physique, a goatee, and a nervous stutter, had seen his brother and most of his brother’s family die. His pal, an extrovert named Thony, spoke in French about this event, which he called l’épidémie, while Sophiano remained mostly glum and silent. It had all begun, Thony explained, with a chimpanzee carcass, found dead in the forest, brought back to the village, and eaten. Everyone who had touched the meat got sick, Thony said. He thought the chimp had been poisoned. I knew it had probably been hot with the virus. Having read some of the scientific literature, I was well aware that Ebola virus kills apes as well as humans. Then suddenly I heard Thony add a macabre detail. Amid all the chaos and horror of the outbreak, he and Sophiano had seen something bizarre: a pile of thirteen dead gorillas, lying nearby in the forest.

Twelve years ago this summer, I sat at a campfire in a Central African forest, hearing the sad, horrific account of an Ebola virus outbreak in a nearby village. My two informants were Bantu men who had lost friends and loved ones in that outbreak. One of them, a shy fellow named Sophiano, with a body-builder’s physique, a goatee, and a nervous stutter, had seen his brother and most of his brother’s family die. His pal, an extrovert named Thony, spoke in French about this event, which he called l’épidémie, while Sophiano remained mostly glum and silent. It had all begun, Thony explained, with a chimpanzee carcass, found dead in the forest, brought back to the village, and eaten. Everyone who had touched the meat got sick, Thony said. He thought the chimp had been poisoned. I knew it had probably been hot with the virus. Having read some of the scientific literature, I was well aware that Ebola virus kills apes as well as humans. Then suddenly I heard Thony add a macabre detail. Amid all the chaos and horror of the outbreak, he and Sophiano had seen something bizarre: a pile of thirteen dead gorillas, lying nearby in the forest.

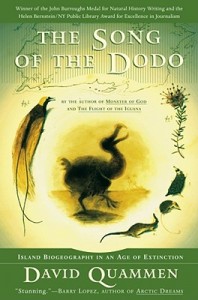

“This is a frightening and fascinating masterpiece of science reporting that reads like a detective story.” — Walter Isaacson. Click on the jacket cover to buy ‘Spillover’ from your local indie.

This moment was the beginning of my journey into the subject of zoonotic diseases. Thony’s throwaway comment, that image, that phrase—“treize gorilles, morts”—was the starting point toward Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic.

About six years later, National Geographic asked me to do a story on zoonotic diseases. This fit well with my ongoing interest in the subject, and I seized the chance. A wonderful photographer named Lynn Johnson was assigned as my partner for the visual side. Lynn specialized in portraying moments of stress in people’s faces, and that well suited her to the subject of disease. She and I traveled to the Republic of the Congo, to follow an expedition led by Dr. Billy Karesh, then of the Wildlife Conservation Society, to tranquilize-dart gorillas in one of the areas that had been much affected by Ebola, in order to see whether the surviving gorillas carried antibodies to the virus; we scouted the forest for eight days and found that there were virtually no surviving gorillas.

Lynn and I also went to northern Australia with a scientist named Raina Plowright, who was trapping bats to look for evidence of their role as reservoir hosts of Hendra, another of the infamous new viruses. Hendra, first discovered in 1994, drips out of bats and gets into horses, evidently when the horses graze on grass bespattered with bat feces and urine. The virus sickens horses gruesomely, causing bloody foam to come up their throats and out their nostrils; it passes from horses into some of the veterinarians, horse trainers and other people who try to save them. The  lethality rate of Hendra virus disease in humans is about 50 percent. During that trip to Australia, I met two survivors (at that time, the only two) of Hendra infection and interviewed them. And, of course, I visited the CDC in Atlanta, for conversations with scientists of the Special Pathogens Branch. These researchers went into the story, titled “Deadly Contact,” that Lynn and I published in National Geographic. At that point, roughly six years ago, I wrote a proposal and signed a contract with W.W. Norton, which had published my two previous books, Monster of God and The Reluctant Mr. Darwin, to do a book on the subject.

lethality rate of Hendra virus disease in humans is about 50 percent. During that trip to Australia, I met two survivors (at that time, the only two) of Hendra infection and interviewed them. And, of course, I visited the CDC in Atlanta, for conversations with scientists of the Special Pathogens Branch. These researchers went into the story, titled “Deadly Contact,” that Lynn and I published in National Geographic. At that point, roughly six years ago, I wrote a proposal and signed a contract with W.W. Norton, which had published my two previous books, Monster of God and The Reluctant Mr. Darwin, to do a book on the subject.

After a bit of groping, I settled happily on the title Spillover. That word describes the moment when a zoonotic disease passes from its animal host into humans.

I continued traveling on assignment for Nat Geo (with whom I’m under contract, as a contributing writer, for three stories a year), and now also for book research toward Spillover. The book work took me back to the forests of Central Africa, back to Australia for more  investigations of Hendra, and to Peninsular Malaysia (for a disease called Nipah encephalitis), Borneo (zoonotic malaria), Bangladesh (with researchers studying the emergence of simian foamy virus from temple monkeys), Uganda (looking into a newly emerged species of Ebola), southern China and Hong Kong (SARS and influenza), back to Bangladesh (Nipah virus there, too), the Netherlands (Q fever, passed to humans from dairy goats), suburban New York (where I watched Lyme disease researchers trapping mice and collecting ticks), ranch land outside of Butte, Montana (hantavirus, in a different species of mice), back to the CDC in Atlanta for more interviews, back to Central Africa (where I retraced the route by which HIV reached the wider world, after spilling over from a single chimpanzee into a single human, in the southeastern corner of Cameroon), and elsewhere.

investigations of Hendra, and to Peninsular Malaysia (for a disease called Nipah encephalitis), Borneo (zoonotic malaria), Bangladesh (with researchers studying the emergence of simian foamy virus from temple monkeys), Uganda (looking into a newly emerged species of Ebola), southern China and Hong Kong (SARS and influenza), back to Bangladesh (Nipah virus there, too), the Netherlands (Q fever, passed to humans from dairy goats), suburban New York (where I watched Lyme disease researchers trapping mice and collecting ticks), ranch land outside of Butte, Montana (hantavirus, in a different species of mice), back to the CDC in Atlanta for more interviews, back to Central Africa (where I retraced the route by which HIV reached the wider world, after spilling over from a single chimpanzee into a single human, in the southeastern corner of Cameroon), and elsewhere.

After about four years of such travels, I started writing the book. Before I finished, though, I made a few more important trips, including one to a pathology lab in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where, behind a blue curtain, I saw the little pantry-like storage area from which a single extremely important tissue sample, containing an HIV-positive bit of human organ extracted from a human during a biopsy in 1960, had provided scientists with a clue that helped reveal just when the AIDS pandemic had begun. The answer was surprising: The virus has been in humans  since 1908 or earlier, give or take a margin of error.

since 1908 or earlier, give or take a margin of error.

I tell the story of that HIV-positive specimen, and the rest of the tale of the origins of AIDS, as illuminated by new scientific discoveries within just the past five years, in my penultimate chapter, “The Chimp and the River.” I think of that chapter as the crescendo of Spillover.

It’s a gruesome and shocking book, in some ways, I suppose—filled with scary new diseases, human misery and death, and a serious note of warning about the potential scope of the Next Big One. But it’s also a work of nonfiction, structured and written with care, and intended to deliver literary satisfaction, a sense of adventure, vivid characters, even a few touches of humor, as well as scientific explanation, analysis and urgent warning. It’s a travelogue, the record of a quest for information and understanding, on which I served as the reader’s proxy. My hope is that Spillover will be received as an important book, a useful book, but not just that. I’ve tried hard to make it read like a guilty pleasure.

Join Quammen in Portland Monday October 22 at 7 pm for a Science Pub evening at the Bagdad Theater.

This is what Halloween feels like for sober adults. I need a drink.