“Who’s your favorite poet?” she asked almost as soon as she entered the bookstore, and I could feel my grimace forming. I hope I stifled it before she noticed. Please understand, I don’t mean to be critical of the several folks each year who ask that question. In fact, I think I understand the impulse behind it. Like those others, this latest questioner wanted to talk about the poetry she loves and to hear me do the same. That’s a conversation I welcome—I’ve spent the last 17 years trying to create a place where such a dialogue is not just tolerated, it’s encouraged.

“Who’s your favorite poet?” she asked almost as soon as she entered the bookstore, and I could feel my grimace forming. I hope I stifled it before she noticed. Please understand, I don’t mean to be critical of the several folks each year who ask that question. In fact, I think I understand the impulse behind it. Like those others, this latest questioner wanted to talk about the poetry she loves and to hear me do the same. That’s a conversation I welcome—I’ve spent the last 17 years trying to create a place where such a dialogue is not just tolerated, it’s encouraged.

But (you knew that was coming, didn’t you?) to squeeze that affection into the narrow box of “favorite poet” has become uncomfortable for me, if not impossible. In part, I resist because if I place a crown on one poet I immediately feel that I’ve banished all the others who’ve given me moments of delight, inspiration, insight, mystery, and transcendence. I suppose this comes with having made something—in this case poetry—a part of my life for so long. My family of poets, which includes the dead and the living, is vast, and I hope to continue to adopt (or rather be adopted) until I no longer can. I guess affection just makes one more affectionate.

Another reason I shy away from declaring a favorite poet is that it’s not the poet that ultimately matters to me, it’s the poem. And since poems exist in time (there you are reading one on your porch or reciting one over the bed of a drowsy child), it’s the time where we meet them—sometimes over and over, sometimes once and fleetingly—that matters. Who can reduce their days to a favorite moment? Life is too variable and rich and filled with potential for that.

Another reason I shy away from declaring a favorite poet is that it’s not the poet that ultimately matters to me, it’s the poem. And since poems exist in time (there you are reading one on your porch or reciting one over the bed of a drowsy child), it’s the time where we meet them—sometimes over and over, sometimes once and fleetingly—that matters. Who can reduce their days to a favorite moment? Life is too variable and rich and filled with potential for that.

So, let’s say that the just-arrived customer instead said, “Tell me about some moments when you’ve savored a poem.” Now that I can do . . .

In 2004, we hosted a reading by the breathtakingly original Alaskan poet Olena Kalytiak Davis. She is an intensely present reader and someone deeply immersed in poetry. From the beginning, it was a riveting evening, made all the more powerful by  the intimacy of our 500-square-foot store. In the middle of her reading, she began to talk about Randall Jarrell’s poem “Seele im Raum,” which she discovered none of us knew. And so she pulled Jarrell’s The Complete Poems from our shelves and read us this stunning poem. In it, Jarrell, an American who lived from 1914 to 1965, writes in the voice of a woman who may or may not have seen an eland (a kind of antelope) eating at the dinner table with her husband and children— “Shall I make sense or shall I tell the truth? / Choose either—I cannot do both.” It is a fearless, heartbreaking piece whose title, taken from a poem by the German writer Rainer Maria Rilke, translates as “soul in the room.” Jarrell’s work has not been much a part of my life, but oh that poem, oh that moment when I met it.

the intimacy of our 500-square-foot store. In the middle of her reading, she began to talk about Randall Jarrell’s poem “Seele im Raum,” which she discovered none of us knew. And so she pulled Jarrell’s The Complete Poems from our shelves and read us this stunning poem. In it, Jarrell, an American who lived from 1914 to 1965, writes in the voice of a woman who may or may not have seen an eland (a kind of antelope) eating at the dinner table with her husband and children— “Shall I make sense or shall I tell the truth? / Choose either—I cannot do both.” It is a fearless, heartbreaking piece whose title, taken from a poem by the German writer Rainer Maria Rilke, translates as “soul in the room.” Jarrell’s work has not been much a part of my life, but oh that poem, oh that moment when I met it.

And here’s another . . .

Though my workplace is filled with books, my workday is not filled with reading them, despite what many imagine. The hours pass with the assisting of customers, the placing of orders, the shipping of packages, the paying of bills. Yes, I sample a poem or two while the door’s unlocked, but even with the romance of literature surrounding me, what I do is work in retail. When I’m in the store, my reading self, the one who immerses herself, is waiting for me elsewhere. Yet there was one afternoon, an almost unnervingly quiet one, when I was working the store alone. After the morning’s one delivery, the door remained unopened, the phone silent. As the hours passed, I could feel myself slipping out of my clerk’s apron and into the reader’s cloak. I picked from the pile of books to be shelved the slim volume Geography III by the American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), a book I’d read years ago in school, and, truth be told, never quite warmed to, the poems too coolly distant and stiffly plain to me. What a blessing it is to be given—to

Though my workplace is filled with books, my workday is not filled with reading them, despite what many imagine. The hours pass with the assisting of customers, the placing of orders, the shipping of packages, the paying of bills. Yes, I sample a poem or two while the door’s unlocked, but even with the romance of literature surrounding me, what I do is work in retail. When I’m in the store, my reading self, the one who immerses herself, is waiting for me elsewhere. Yet there was one afternoon, an almost unnervingly quiet one, when I was working the store alone. After the morning’s one delivery, the door remained unopened, the phone silent. As the hours passed, I could feel myself slipping out of my clerk’s apron and into the reader’s cloak. I picked from the pile of books to be shelved the slim volume Geography III by the American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), a book I’d read years ago in school, and, truth be told, never quite warmed to, the poems too coolly distant and stiffly plain to me. What a blessing it is to be given—to  give oneself—a second (or third or twentieth) opportunity to meet a poem. Settled in the silent space of the shop, I moved through the book, amazed at its grace, its intelligence, its glints of sadness and ripples of kindness. At the middle of the book is one of Bishop’s most famous poems, “The Moose,” and I read it as if for the first time—well, it was the first time in my skin of that moment. In it, the poet describes a bus trip interrupted by the brief appearance of a moose—”Taking her time, / she looks the bus over, / grand, otherworldly. / Why, why do we feel / (we all feel) this sweet / sensation of joy?” Thank you for waiting for me, Miss Bishop.

give oneself—a second (or third or twentieth) opportunity to meet a poem. Settled in the silent space of the shop, I moved through the book, amazed at its grace, its intelligence, its glints of sadness and ripples of kindness. At the middle of the book is one of Bishop’s most famous poems, “The Moose,” and I read it as if for the first time—well, it was the first time in my skin of that moment. In it, the poet describes a bus trip interrupted by the brief appearance of a moose—”Taking her time, / she looks the bus over, / grand, otherworldly. / Why, why do we feel / (we all feel) this sweet / sensation of joy?” Thank you for waiting for me, Miss Bishop.

And another . . .

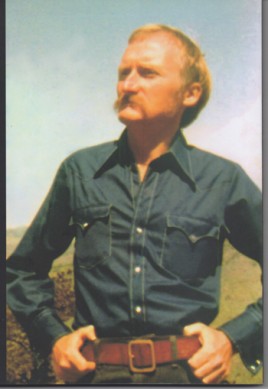

At the end of each year, we (meaning my partner-in-all things, John W. Marshall, and I) perform a physical inventory of the bookstore, a task that is dictated by tax law and as revealing (sometimes painfully so) as it is mind-numbingly tedious. For several days, we close the store (except for poetry emergencies) and tally the number and price of all 10,000-plus books on our shelves. One of us, sitting in a chair (not too comfy or drowsing ensues), makes hash marks on a price list while the other, balanced on a stool or crouched on aging knees says/shouts/sings, “15.95, 22.50, two at 12.95, 65 dollars,” and on and on. As you might imagine, by the time we reach the U’s, we’re pretty rummy or grumpy, or both. A couple of years ago, when we were at that physical and psychological point, John pulled out the copy of The March to the Stars by the Romanian poet Mihai Ursachi (1941-2004), whose author  photo was just too compelling not to serve as a welcome distraction. Despite having been face-to-photo with Ursachi over the years, I had yet to open his book. John handed it to me, suggesting a page, and I read aloud “Three Poems on Behalf of Ants.” Touching, surreal, and playfully dark in the way of much Eastern European writing, those poems were a tonic—”Have you ever heard the song of the ant? / Nobody hears it, nobody hears it.” We were lifted, charmed, and reminded of the wonderfully strange treasures around us. That moment was why we live a life that includes the drudgery of inventory.

photo was just too compelling not to serve as a welcome distraction. Despite having been face-to-photo with Ursachi over the years, I had yet to open his book. John handed it to me, suggesting a page, and I read aloud “Three Poems on Behalf of Ants.” Touching, surreal, and playfully dark in the way of much Eastern European writing, those poems were a tonic—”Have you ever heard the song of the ant? / Nobody hears it, nobody hears it.” We were lifted, charmed, and reminded of the wonderfully strange treasures around us. That moment was why we live a life that includes the drudgery of inventory.

And another time—no, that’s enough from me. I imagine (hope) that at this point your own moments of savoring are rising in memory. Tell me about them.

Christine Deavel co-owns Open Books: A Poem Emporium, one of two poetry-only bookstores in the United States. Her collection of poetry, Woodnote, was published in 2011.

Just this afternoon I recounted my reintroduction to poetry, while chatting about William Hjortsberg’s exhaustive new biography of Richard Brautigan. I only had a few weeks or months under my belt as a bookseller when a coworker suggested that I read The Pill Versus the Spring Hill Mine Disaster. “Oh. I don’t really like poetry,” I said, setting it down after a quick glance. A bit of badgering ensued, so I opened the book and selected a poem at random called The Pumpkin Tide. I was immediately smitten with the lighthearted tone and simple imagery, and I felt like a light bulb that had been burnt out since high school was at last replaced.