Trying to introduce Cheryl Strayed reminds us of what she wrote in her Pushcart Prize-winning essay Munro Country, about meeting Alice Munro for the first time and fumbling over what to say to the fiction icon who she’s long admired. She finally concludes there’s “both too much and nothing to say.” You really have to read Strayed’s nonfiction writing to understand her honest, elegant style. Some people never get that candid with their closest friends, and yet there’s no yucky therapy quality; you just feel like her best friend. For the uninitiated, we suggest an afternoon off and a look at her essays and her columns as Dear Sugar, the Rumpus’s beloved truth warrioring advice columnist.

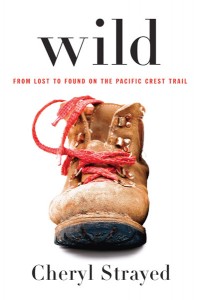

Strayed recently revealed herself as Sugar after two years of relative anonymity, a smart move just a month before the release of her memoir Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail. For those who know Strayed’s work, Wild covers some familiar territory about her mother’s death, the dissolution of her first marriage and a shaky time in her life. But it’s mostly the story of a journey—an outward one of survival on a grueling trail that bests even accomplished hikers and an inward one to rebuild herself after hitting bottom in her early twenties. It’s a deceptively effortless read given all that weight—and one that’s often funny and full of well-rendered ordinary moments. Wild comes out on March 20 and has already been optioned for a film by Reese Witherspoon’s production company. A collection of Strayed’s writing as Sugar, Tiny Beautiful Things, will be published in July.

Strayed’s debut novel, Torch, was a finalist for the Great Lakes Book Award and was selected by The Oregonian as one of the top ten books of 2006 by an author from the Pacific Northwest.

She lives in Portland with her husband, the filmmaker Brian Lindstrom, and their two children. NWBL’s Jamie Passaro emailed with her between her Sugar coming-out parties and her tour for Wild. She answered questions generously and admitted, not surprisingly, that she’s already tired. Strayed will kick off her book tour at Powell’s on Wednesday, March 21 at 7:30 pm. She’ll tour again when Tiny Beautiful Things is published in July. Check out her events schedule here.

Will you play bookseller and build us a display around Wild? What a great question! I’d first include the books written by the authors in my writing group—Monica Drake, Chelsea Cain, Lidia Yuknavitch and Chuck Palahniuk. All of them, along with the other fabulous writers in our group, gave me important feedback as I wrote Wild.

Will you play bookseller and build us a display around Wild? What a great question! I’d first include the books written by the authors in my writing group—Monica Drake, Chelsea Cain, Lidia Yuknavitch and Chuck Palahniuk. All of them, along with the other fabulous writers in our group, gave me important feedback as I wrote Wild.

Next, I’d include the books I named in Wild—those I packed along with me and read on my hike and then burned in order to lighten my load. They include Lolita and As I Lay Dying, Flannery O’Connor’s Complete Stories and Adrienne Rich’s The Dream of a Common Language, among many others. John Muir’s books would be there, as would the PCT guidebooks published by Wilderness Press. Lastly, I’d include two memoirs about walking a long way: Dan White’s The Cactus Eaters, about his PCT hike, and Alexandra David-Néel’s My Journey to Llasa, which is truly one of the most astounding books ever written about a journey of any kind.

You must be a seriously stubborn person to have hiked 1,100 miles—Mojave, California to Bridge of the Gods over the Columbia River. You had never backpacked before and yet you prevailed through ice and snow, near dehydration, bloodied and blistered toes, hips and shoulders, carrying a backpack so big and heavy you named it Monster. Would you say that that same willfulness serves you as a writer? And how? That willfulness absolutely serves me as a writer. So much of a writer’s work is like a long backpacking trip. You have to keep going even if it hurts or feels tedious. You have to take each step one by one and yet always keep the destination in mind. You can’t let the bad days stop you or allow the good days to make you an asshole. There’s always something new to learn. The work will teach  you what it is. The lesson is revealed in course of the journey. I’m quite sure persistence is the quality that played the most important role in my both my literary and wilderness endeavors.

you what it is. The lesson is revealed in course of the journey. I’m quite sure persistence is the quality that played the most important role in my both my literary and wilderness endeavors.

Wild has an obvious appeal to memoir lovers, and it will also appeal to anyone who’s ever had anything to do with the Pacific Crest Trail. Did you have a reader in mind when you wrote it? Do you usually write with someone in mind? I don’t write with any one sort of reader in mind. I write for my own internal reader. She’s generally a damning wench.

If you mapped the brains of some of the best writers, you’d probably find that the internal wench zone is  always highly developed. Is that self criticism ever a hindrance to your writing process? I think it would be a greater hindrance if I sat around thinking, “oh my goodness, I’m brilliant!”

always highly developed. Is that self criticism ever a hindrance to your writing process? I think it would be a greater hindrance if I sat around thinking, “oh my goodness, I’m brilliant!”

To write well, you need to be able to say no to yourself. But sometimes you can get stuck in the internal wench zone. It’s usually quite difficult for me to begin writing something. I stare at the blank screen and think all these self-loathing thoughts. One has to simply begin in spite of them.

You say in your author’s note in Wild that you kept journals along the way, but how does what you write in the journals differ from what we’re reading now in Wild? Wild is a polished, crafted memoir—a book—while my journals are private letters to  myself. They are sketches of the day that I wrote with no audience or artistic or publishing goals in mind. The journal I kept while hiking the PCT was a great resource to me in writing Wild because I’d documented so much of what happened and when. Often, I recorded conversations only minutes after they occurred or noted aspects of the landscape I’d have forgotten if I had only my memory to rely on. But I wasn’t writing that journal in order to someday write a book. It was just what I did. I kept journals all through my twenties and into my thirties. When I became a mother I simply didn’t have time to do that sort of writing with any regularity, so my journaling fell away. It’s painful and fascinating for me to read the journals from my twenties. I now have a sort of maternal feeling about the young woman in the pages of those old journals those pages. That young woman was suffering enormously, but she was always reaching for the light. If I could go back in time I would tell her it’s all going to be okay. I feel like I do that a lot in my “Dear

myself. They are sketches of the day that I wrote with no audience or artistic or publishing goals in mind. The journal I kept while hiking the PCT was a great resource to me in writing Wild because I’d documented so much of what happened and when. Often, I recorded conversations only minutes after they occurred or noted aspects of the landscape I’d have forgotten if I had only my memory to rely on. But I wasn’t writing that journal in order to someday write a book. It was just what I did. I kept journals all through my twenties and into my thirties. When I became a mother I simply didn’t have time to do that sort of writing with any regularity, so my journaling fell away. It’s painful and fascinating for me to read the journals from my twenties. I now have a sort of maternal feeling about the young woman in the pages of those old journals those pages. That young woman was suffering enormously, but she was always reaching for the light. If I could go back in time I would tell her it’s all going to be okay. I feel like I do that a lot in my “Dear  Sugar” columns.

Sugar” columns.

The first essay I read of yours was Heroin/e, which was published first in Doubletake and then in Best American Essays 2000. It’s about desire: your mother’s craving for morphine in the last weeks of her battle with cancer and your grief and plunge into heroine abuse after her death. Four years after her death, you set out on the PCT. It was what you now describe as “the bottom of my life.” At what point in your life were you ready to start writing and publishing about this time and how did you know? When my mother died I began writing about her death and my grief  immediately. I wasn’t writing to be published—I was only 22, so I was just developing as a writer—but I was writing about it because I couldn’t not write about it. There was honestly nothing else to say. What on earth would there have been to say but my mother is dead and I cannot bear it? It was the only thing worth writing about. I was a senior in college when my mother died and the wonderful writer Paulette Bates Alden was a mentor to me at the time.

immediately. I wasn’t writing to be published—I was only 22, so I was just developing as a writer—but I was writing about it because I couldn’t not write about it. There was honestly nothing else to say. What on earth would there have been to say but my mother is dead and I cannot bear it? It was the only thing worth writing about. I was a senior in college when my mother died and the wonderful writer Paulette Bates Alden was a mentor to me at the time.

I just loved her entirely—her writing, her spirit, the way she was in the world. I wanted her to be impressed with me. I remember very distinctly going into her office about ten days after my mom died and feeling like I should be okay by then, like I shouldn’t cry while I talked to her because to cry was weak. But the minute she saw me, she started crying herself. She made me tea and she told me that I  shouldn’t worry about what I was writing, that I should write whatever I wanted, whether it be about my mother or not. I thought of that so often as I wrote through the years, almost always about my mother. Paulette’s kind words gave me permission.

shouldn’t worry about what I was writing, that I should write whatever I wanted, whether it be about my mother or not. I thought of that so often as I wrote through the years, almost always about my mother. Paulette’s kind words gave me permission.

So I wrote about my mom. A lot of it was terribly dark and self-pitying. A lot of it overly idealized my mother. She was my hero, and yet she was not entirely heroic—like all of us. I had to reach a place of maturity and self-awareness and acceptance before I could write anything worth showing to anyone else—about my mother, or frankly about anything. I don’t believe writers should be in a great rush to publish. I think publishing can ruin your writing if you do it before the work is really ready. My big dream of my early twenties was to have a book published by 30, but I am deeply glad that didn’t come to pass.

Heroin/e was my first essay. I wrote it in one day, on July 4, 1997. I was in residence at the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, New Mexico, writing the very beginnings of what would become my first book—a novel called Torch—and I awoke at dawn that morning horrified that I’d forgotten who my actual mother was because I was fictionalizing her in my novel. I decided to spend the day writing the true story of her death. I wrote for 13 or 14 hours almost without stop. When I finished, I sobbed.

Heroin/e was my first essay. I wrote it in one day, on July 4, 1997. I was in residence at the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, New Mexico, writing the very beginnings of what would become my first book—a novel called Torch—and I awoke at dawn that morning horrified that I’d forgotten who my actual mother was because I was fictionalizing her in my novel. I decided to spend the day writing the true story of her death. I wrote for 13 or 14 hours almost without stop. When I finished, I sobbed.

‘I’ve made it to the other side of this’ is a big theme in your writing. But can you ever write about something that you’re in at the moment? I think it depends on the memoir, but I’d say as a general rule the passage of time is beneficial to the work. It allows a writer to gain perspective on the experience and that’s what memoir is really about—not what happened, but rather the consciousness the writer brings to bear on what happened. The amount of time one needs to gain that consciousness varies widely.

It makes me wonder what we’ll see in your writing of this period in your life, when you’re “settled down” with a husband and two kids and the writing career you’ve always wanted. Do you think you’ll continue to write about the stuff that happened in your twenties or that you’ll one day be writing about what’s happening in your life now? I often joke the sequel to Wild will be called Mild, but of course I’m exaggerating. My twenties are rich with emotional turmoil and big life changes. My thirties and forties have been rich with those things too, but perhaps with a bit less drama. I think I’ll always write about my twenties, but stories about more recent years are also of interest to me. I’ve written about those years in my “Dear Sugar” columns and also in a few essays. More will come over the years, I’m sure.

You’ve always been incredibly open about your personal life, and that’s one of the reasons your writing is appealing. What makes you so brave about that—and what are some of your guidelines about what you will and won’t write about? I’m always struck when people say that about my openness—and they always say that!—because I honestly can’t think of another way to write. I can’t imagine writing from a place that’s closed off or scared, that conceals rather than reveals. That would never occur to me. To me the whole deal with writing is to dig into what’s true, to put on the page what one cannot bear to say or see or know. I’m not interested in writing that doesn’t do that. Having said that, when writing nonfiction, I try to protect those I write about. When I have to write something difficult or unflattering about another person, I obscure his or her identity when possible and I write only what is necessary. If I’m going to show someone’s ass, I make sure I’ve shown my own first.

You’ve always been incredibly open about your personal life, and that’s one of the reasons your writing is appealing. What makes you so brave about that—and what are some of your guidelines about what you will and won’t write about? I’m always struck when people say that about my openness—and they always say that!—because I honestly can’t think of another way to write. I can’t imagine writing from a place that’s closed off or scared, that conceals rather than reveals. That would never occur to me. To me the whole deal with writing is to dig into what’s true, to put on the page what one cannot bear to say or see or know. I’m not interested in writing that doesn’t do that. Having said that, when writing nonfiction, I try to protect those I write about. When I have to write something difficult or unflattering about another person, I obscure his or her identity when possible and I write only what is necessary. If I’m going to show someone’s ass, I make sure I’ve shown my own first.

Sure, you’ve got to expose yourself and your internal wench and all your vulnerabilities; that’s what makes your writing so relatable. “Write like a motherfucker” as Sugar says. That’s one thing. But putting it out there, opening yourself up to all sorts of criticism—from the literary kind to your mother-in-law to the mail carrier. Do you ever lose any sleep over that? Does it ever wear you out? Absolutely! I’m terrified. In the past when I’ve heard writers say they don’t read the reviews of their books I thought there was no way on earth I’d ever do that, but recently I’ve followed their lead. I do read some reviews, but it’s an uncomfortable experience, even when the words are positive and supportive, so I’ve found it best to try to avoid them. With a memoir, people aren’t only critiquing a book. They’re critiquing a life. I feel vulnerable, scared, exposed. I’m not sleeping well. This, and yet I’m also wildly excited to bring Wild into the world. I want everyone to read it. I just want to be in a cave in the far reaches of Iceland when they discuss it amongst themselves.

Sure, you’ve got to expose yourself and your internal wench and all your vulnerabilities; that’s what makes your writing so relatable. “Write like a motherfucker” as Sugar says. That’s one thing. But putting it out there, opening yourself up to all sorts of criticism—from the literary kind to your mother-in-law to the mail carrier. Do you ever lose any sleep over that? Does it ever wear you out? Absolutely! I’m terrified. In the past when I’ve heard writers say they don’t read the reviews of their books I thought there was no way on earth I’d ever do that, but recently I’ve followed their lead. I do read some reviews, but it’s an uncomfortable experience, even when the words are positive and supportive, so I’ve found it best to try to avoid them. With a memoir, people aren’t only critiquing a book. They’re critiquing a life. I feel vulnerable, scared, exposed. I’m not sleeping well. This, and yet I’m also wildly excited to bring Wild into the world. I want everyone to read it. I just want to be in a cave in the far reaches of Iceland when they discuss it amongst themselves.

A lot of people feel like they know you even though you don’t have an actual relationship with them beyond that of writer and reader. Does that get uncomfortable sometimes? Uncomfortable isn’t the word. I’m truly touched by the many people who share their stories with me based on something I wrote, but it’s certainly intense at times to have so many readers feel so connected to me personally. It’s both rewarding and daunting to take it all in, to listen and make the speaker feel acknowledged and heard, to invest in the story beyond what’s on the page. Mostly, I feel grateful when anyone is moved to talk to me about something I wrote. I understand why people feel like they know me after they read my work. I feel the same way about many of the writers I most love.

You’re a champion for other writers, other women especially. You’re like a bookseller in that regard, recommending the work of others on your Facebook page and elsewhere. There are certain people who have a knack for this—and a need to share what they love. Where do you think that impulse comes from? That impulse comes from my natural desire to be kind to and supportive of my fellow writers and my real love and admiration for the things they’ve written. I want to share good things. I have so much fun saying “okay, friends, read this!” I do it so much on my Facebook page that every now and then a writer will ask me to post about something he or she wrote, but I don’t usually do that. My Facebook page isn’t a marketing platform. I don’t write advertisements. My recommendations have to come from a genuine place or they’re not recommendations. Booksellers know this. That’s why we need them.

What have you read recently that you love? Marcia Aldrich’s forthcoming memoir, Companion to an Untold Story, which will be published by the University of Georgia Press this fall. It’s a gorgeously written, geniusly structured tale about a friend of Aldrich’s who committed suicide. I loved it. Also, Pam Houston’s latest, a fabulous novel called Contents May Have Shifted. I’ve been a Pam Houston fan since I was that kid trying not to cry in Paulette Bates Alden’s office. She’s only gotten better, smarter, wiser.

What a great interview! Cheryl’s creative display ideas are particularly useful. Add a canteen, some old hiking boots, and a tent as a backdrop and we all have a perfect window display for the next month. Sideline ideas for the display: CLIFF bars, water bottles, and bandannas. 🙂

Thanks, Tegan! We hope lots of stores will build a display around Cheryl’s ideas. Someone ought to offer a display contest. We can think of some pretty fun Wild-inspired prizes. Random House, are you listening?

Wonderful to read this! Jamie, it’s so right on to call Cheryl’s style honest and elegant, with “no yucky therapy quality.” Thanks to both of you…

[…] Companion to an Untold Story by Marcia Aldrich. University of Georgia Press, 262 pp. It’s a gorgeously written, geniusly structured tale about a friend of Aldrich’s who committed suicide. I loved it.—Cheryl Strayed, in an interview […]