Months after graduating from Oregon State University, Eugene native Noah Strycker was helicoptered in to a remote Antarctic field camp with two other bird scientists and a three-month supply of frozen food. Among Penguins: A Bird Man in Antarctica (OSU Press) is his memoir of what it’s like to be 22 and living life in a tent at the end of the Earth.

Months after graduating from Oregon State University, Eugene native Noah Strycker was helicoptered in to a remote Antarctic field camp with two other bird scientists and a three-month supply of frozen food. Among Penguins: A Bird Man in Antarctica (OSU Press) is his memoir of what it’s like to be 22 and living life in a tent at the end of the Earth.

Strycker first developed his interest in birds in fifth grade, and by the time he was 19, he was associate editor of Birding magazine, a columnist for WildBird, and a book reviewer for Birder’s World. He has traveled widely to observe and document birds and has contributed original illustrations and photographs for books and articles.

When we first emailed with Strycker he was on another bird assignment, this time in Costa Rica banding birds with the Costa Rica Bird Observatories. He’s back in Oregon now, getting ready to go on a book signing tour. Ever the adventurer, he’s also thinking about hiking the 2,650-mile Pacific Crest Trail, from Mexico to Canada, over the summer before finding another field job in the fall.

We asked Strycker some questions about his nomadic life as a “bird bum.”

Why did you want to go to Antarctica? Antarctica fascinated me because of its remote setting, extreme environment, and, of course, penguins. It’s funny, I knew it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity but about half the people I shared it with just raised their eyebrows. I guess not everyone has the same sense of adventure as I do.

Why did you want to go to Antarctica? Antarctica fascinated me because of its remote setting, extreme environment, and, of course, penguins. It’s funny, I knew it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity but about half the people I shared it with just raised their eyebrows. I guess not everyone has the same sense of adventure as I do.

You were into birds early on, and in middle and high school you were known as “that bird kid.” How did you develop your interest? My fifth-grade teacher put a plastic bird feeder on our classroom window and stopped class whenever a cool bird showed up. I enlisted my dad to help me build 30 birdhouses at home, and started identifying birds in my own backyard. From there, birds were like any other addiction. I met a group of like-minded people who took trips for the sole purpose of looking at birds, and, for me, there was no going back.

You’ve managed to make a career out of studying birds all over the world, being a “bird bum” as you call yourself. How did you turn your passion into a career? Basically, I’ve decided to follow my dream, which is to follow birds. I took a year off between high school and college to travel in search of birds, and it was the best thing I ever did; it made me realize what was really important to me. I spent every summer during college studying birds in different places, and, after I graduated, it just continued except full-time and broader-scale. I don’t consider birding to be a job, more like a lifestyle. So far, it’s treating me very well.

You’ve managed to make a career out of studying birds all over the world, being a “bird bum” as you call yourself. How did you turn your passion into a career? Basically, I’ve decided to follow my dream, which is to follow birds. I took a year off between high school and college to travel in search of birds, and it was the best thing I ever did; it made me realize what was really important to me. I spent every summer during college studying birds in different places, and, after I graduated, it just continued except full-time and broader-scale. I don’t consider birding to be a job, more like a lifestyle. So far, it’s treating me very well.

Where are some of the other places birds have taken you? I have spent field seasons (3-5 months each) working with birds in Hawaii, Antarctica, California (Point Reyes and the Farallon Islands), the Australian Outback, the Galapagos, Panama, Maine, Michigan, Oregon, and Costa Rica, and have visited a few more countries in search of birds. The only continent I haven’t visited yet is Africa, and I want to go! The great thing about birds is that they are distributed globally; the more places you visit, the more birds you’ll see, and I want to study as many as possible.

What are some of the most interesting things you learned about penguins while studying them? I learned that penguin mummies never decompose in the frost, they can be thousands of years old, and they’re absolutely everywhere on the ground crunching underfoot in the penguin colony. I learned that penguins return to the same exact nest year after year. I learned that rare all-black and albino penguins can find love, though it can be hard for them. I learned how to capture a penguin (you just walk over and pick it up!). And I learned that these birds, living at the coldest edges of Earth, are actually under threat from global warming, and their well-being can tell us a lot about climate change.

How are the penguins reacting to climate change? So far, southern colonies of Adelie Penguins are booming (increasing in population) while northern ones are decreasing. Penguins seem to be moving south as the world warms up. For now, Adelie Penguins are doing OK, but their world of ice is looking at a world of warmth, which can’t be good.

How did you deal with the isolation? It was interesting to spend three months on the ice with just two other researchers to talk to. We got along great, which was fantastic. I spent many hours alone working in the penguin colony, resighting banded birds, and sometimes reached a sort of zen state where I was utterly disconnected from the world and, at the same time, utterly happy. But isolation can only go so far, and it was nice to have a full-time satellite internet connection to stay in touch by email and blog.

How about the cold? The cold wasn’t really an issue. Though it was 20 degrees below zero most of the time and I slept in an unheated canvas tent, on a sleeping pad on solid ice, I was always wearing almost 20 pounds of extreme cold-weather clothing. Though I sometimes felt like a snowman in all those layers, and I once went five weeks without changing my underwear, I was toasty warm.

slept in an unheated canvas tent, on a sleeping pad on solid ice, I was always wearing almost 20 pounds of extreme cold-weather clothing. Though I sometimes felt like a snowman in all those layers, and I once went five weeks without changing my underwear, I was toasty warm.

What did you miss from civilization and what didn’t you miss? Most of all, I missed fresh food: fruits, vegetables, pretty much anything you’d find in your refrigerator. We had a three-month supply of canned food and frozen meat (stuck outside in the snow), but that stuff only goes so far. I also missed a shower—I didn’t bathe for three months—and my face missed a shave, which was good because the beard kept me warm. Of course, I missed friends and family, but knew I’d see them again soon. I definitely didn’t miss working indoors —offices give me headaches!—and I was very happy to have life simplified to its bare necessities.

What are some of the things you did to pass the time? What did you read? I read Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s adventure tale, The Worst Journey in the World, about a fateful trip to Cape Crozier in the early 1900s, while living at Cape Crozier. It was interesting, but sort of scary. While living in an extreme environment, it’s hard to read about people freezing to death in the very same place. Maybe I should have read something more tropical, and saved the Antarctica narrative for a season in the tropics.

What are some of the things you did to pass the time? What did you read? I read Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s adventure tale, The Worst Journey in the World, about a fateful trip to Cape Crozier in the early 1900s, while living at Cape Crozier. It was interesting, but sort of scary. While living in an extreme environment, it’s hard to read about people freezing to death in the very same place. Maybe I should have read something more tropical, and saved the Antarctica narrative for a season in the tropics.

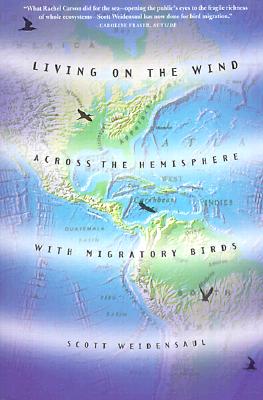

Will you recommend some other books about birds or birding? Kenn Kaufman’s Kingbird Highway is a classic that I’ve read many times. And Scott Weidensaul’s Living on the Wind, about bird migration, is fascinating.

Will you recommend some other books about birds or birding? Kenn Kaufman’s Kingbird Highway is a classic that I’ve read many times. And Scott Weidensaul’s Living on the Wind, about bird migration, is fascinating.

When did you know that your trip would become a book and how did the writing process go? I kept a blog during my time in Antarctica and was very flattered when I was asked to write the book. A couple weeks after returning home from Antarctica, I broke my leg in a skiing accident on Mount Bachelor and spent the following two months in a cast and crutches. The enforced captivity was just what I needed to focus on writing the book, so it kind of worked out.

Stryker’s book tour includes stops at Annie Bloom’s Books in Portland April 12 at 7pm; at the Portland Audubon Nature Store April 20 at 7pm; and Tsunami Books in Eugene April 28 at 7pm.