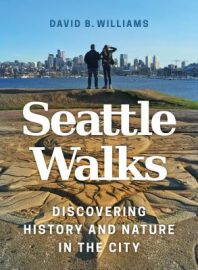

Readers who remember my interview with natural history writer David B. Williams already know that he’s at the very top of the list when it comes to covering our region’s past. His study of the myriad modifications our ancestors have made to the local landscape, Too High and Too Steep, was an Island Books Top Ten Non-Fiction Favorite in 2015 (and is newly out in paperback–run, don’t walk to buy it). Turns out he’s no slouch at addressing the present, either. His latest book is Seattle Walks, a guide to the fairest city on Puget Sound and all the wonders it proffers to the attentive pedestrian. As soon as I heard about it I knew I’d have to road-test … er, sidewalk-test it for myself. I further knew that the smartest way to do it was to bring along someone way more knowledgeable than me about the intersection between the urban and natural environment, someone who’s done plenty of his own writing on the subject. So I invited my friend Matt Fleagle to join me. That was an easy decision, but I dithered a bit about which path we should take. When I bumped into someone carrying the book in hand while exploring my own neighborhood–my building happens to lie along one of the suggested routes–I was roused to immediate action. By which I mean I punted to Matt. He made the call, we went for a walk, and our conversation about it is below.

Readers who remember my interview with natural history writer David B. Williams already know that he’s at the very top of the list when it comes to covering our region’s past. His study of the myriad modifications our ancestors have made to the local landscape, Too High and Too Steep, was an Island Books Top Ten Non-Fiction Favorite in 2015 (and is newly out in paperback–run, don’t walk to buy it). Turns out he’s no slouch at addressing the present, either. His latest book is Seattle Walks, a guide to the fairest city on Puget Sound and all the wonders it proffers to the attentive pedestrian. As soon as I heard about it I knew I’d have to road-test … er, sidewalk-test it for myself. I further knew that the smartest way to do it was to bring along someone way more knowledgeable than me about the intersection between the urban and natural environment, someone who’s done plenty of his own writing on the subject. So I invited my friend Matt Fleagle to join me. That was an easy decision, but I dithered a bit about which path we should take. When I bumped into someone carrying the book in hand while exploring my own neighborhood–my building happens to lie along one of the suggested routes–I was roused to immediate action. By which I mean I punted to Matt. He made the call, we went for a walk, and our conversation about it is below.

————————————————————-

Matt: What interested me about taking David B. Williams’ book out for a test drive was finding out how well it really worked on the road. And by that I mean two very distinct things.

Matt: What interested me about taking David B. Williams’ book out for a test drive was finding out how well it really worked on the road. And by that I mean two very distinct things.

Firstly, I mean how well the walks work as walks rather than as topics in a book. I love reading about history, which is properly done sitting in a comfy chair, as you know, next to a big window with a steaming mug of coffee at hand. And Williams is an engaging writer who does his homework and packs the history into his books with a trowel. Accordingly, I could have enjoyed the whole book without ever leaving my living room, nor even coming out from under the afghan. But it’s a book about walks; walks you are expected to take, and what is interesting in the chair may not necessarily be interesting with the rain dripping into your collar, and it may not even be interesting on a clear, dry day with dulcet spring breezes wafting under your nose. Sometimes history is visible and sometimes it is not. When it is not, a pure skeptic might conclude that there is no point in going to look at it. But I am not a pure skeptic, I am a skeptical believer; I always cherish hope.

Secondly, I mean how well does the book, the physical tome, work as a book and a guide when you take it out into the elements. Again, paper fares better in indoor climes than under the ravages of rain and wind and being stuffed into and hauled out of a backpack. My copy slid out from my embrace under my rain jacket while I was crossing a street and bounced and skittered across the asphalt. It suffered only a little rubbing at the corner, but you see what I mean. It can happen like that.

Incredibly cool, indeed!

You kindly left the choice of which walk to me. The choices range from short circles in Seattle’s downtown core to longer ravine crawls, pond and lake loops, and littoral rambles further out (almost all of the walks feature water tangentially or centrally). I chose Walk 16, “Delridge and Pigeon Point: The Lesser-Known Side of West Seattle,” because it seemed like a walk about which people might more frequently ask, “Why the hell would you spend several hours of your precious Saturday walking around there?” Fewer would ask that of someone setting out to explore the erstwhile naval base at Magnuson Park (Walk 12) or retrace the old trolley route along Madison Street (Walk 7), or cross over the locks on the ship canal (Walk 9), or admire Capitol Hill’s posh fin de siècle houses (Walk 13), or study the stonework gargoyles on the buildings downtown (Walk 5), or take in the views across Puget Sound from Alki Point (Walk 17), where European settlement of the city began. Our goal was to be able to respond to that question with an answer of substance.

Wild West Seattle: Maybe home to beaver?

I read the chapter first (yes, in the chair), and was assured thereby that there would be plenty to see if we took this route. At 4.4 miles, the Delridge walk was one of the longest ones–only three in the book are longer–and there are, Williams admits in a note right at the beginning, “some stretches without formal information.” I think this is an understatement. Hell, much of this tour is just walking along a residential sidewalk waking up the neighbors. But as Williams also notes, there is still plenty to notice and enjoy, and this is also an understatement. This walk has lots of old houses in it, like many arbitrary moseys in Seattle, but it also has some unusual topography, wildlife in the form of salmon (in season) and a beaver dam (the rodent’s lodge appears to have been washed away), a marvelous garden

Fanciful art along the route

and arboretum at the college, and some impressive and fanciful installations of public art.

James: It’s true that this walk included a couple of fallow stretches, but I was glad of them. They gave us a chance to absorb the sights we saw and comment on them, and they also encouraged us to look around for our own discoveries. For example, that thriving co-housing community we passed by, something that Williams mentions only in passing. A charming, intentional country village in the middle of the city–who woulda thunk? If we hadn’t been looking for something to look at we wouldn’t have seen it, wouldn’t have detoured through it, wouldn’t have chatted with one of the residents, and wouldn’t have been offered hand-wrapped packages of quinoa to take home. I know that sounds like something I made up, but it really happened. Didn’t it?

You mention in a general way the many old buildings worth noticing; the highlight among these for me was the former church, former union hall, and current recording studio that occupies a corner near the end of the stroll. It’s exactly the kind of place I’m glad I know something about now, and I wouldn’t if not for Williams. The standout piece of art was probably the massive dragonfly that hovered over a park. That would have been hard to miss in any case, but I wouldn’t have realized that the insect motif was repeated on an even larger scale in the surrounding gardens if the book hadn’t pointed it out to me.

Speaking of gardens, the sheer amount of greenery we saw was amazing. Much of it was more or less groomed in private yards and parks, but there’s far more undeveloped land tucked away in this city than I thought. Room for squirrels, sure, but beavers? Wow. As an urbanite who more easily recognizes different grades of pavement concrete than types of plants, and especially as a book nerd, I very much appreciated the George Cooper poem carved into the strategically scattered boulders at one park entrance: “The Chestnuts came in yellow, / The Oaks in crimson dressed; / The lovely Misses Maple / In scarlet looked their best …” Label and literature all in one, and perhaps slightly more highbrow than the Rush lyrics I would have chosen.

A striking little bridge along the walk

I could go on, but it seems I’m in danger of talking too much about our walk and not enough about the book that got us started. Segue back to the point for me, please.

Matt: How did the book do on this tour? The walk worked for me both as a reading experience and as a physical adventure. But here we come – as John Barth would say – to the gizzard of the thing: if you like to amble and you are interested in the world at all, and if you can abide the fickleties of weather, then you will probably enjoy this or any other walk anywhere. You and I, James, are I think both the kind of people who are not easily bored. And we noticed plenty of things that would not have been worth calling out in the book: there was the intrusion of very new houses among very old ones that engendered a conversation that wove throughout the entire walk about the nature of change in neighborhoods (and actually Williams did touch on this), and there was the fragrance of the osmanthus bushes in bloom in several yards and in the botanical garden, and there was that corner in the Pigeon Point neighborhood where we suddenly noticed a host of birds chattering. And do you remember the pileated woodpecker that we heard squawking in the woods and then saw fly to a utility pole? If these kinds of things don’t interest a person, then the book would have to stand or fall on its “corner chair” merits alone. For me, it stands that test as well.

As a physical, take-along guide, my only complaint is that some of the fonts are so tiny that I could not easily read them while trying to decide which way to turn, which path to take, how far down a stairway we should go. Since I had studied the chapter ahead of time and looked at maps, I pretty much knew my way all along the route, but if I’d had to use the waypoint-by-waypoint instructions in the book without having prepared, my bad eyesight and the small fonts would have made the going a lot more difficult.

James: I feel you, as the kids put it, but I hate to say this is more likely a problem with our aging vision than with the book itself. Our eyes may not be getting any younger, but the good news is that if we keep walking, at least the rest of us will stay healthy. I’m game if you are.

When the public maps are this challenging to read, it’s particularly good to be carrying one’s SEATTLE WALKS book.

James Crossley is a bookseller at Island Books on Mercer Island, WA. When he’s not reading, walking, or reading and walking, you might find him enjoying his Indie Bookstore Champion status at bookstores around the Seattle area.

Usually, James, you leave me researching obscure literary references. This time, watching Rush videos. Hatchet, axe, and saw — you’re a multi-threat artist, sir.